Judith Adelmann, Rachel Fäth, Sophia Mainka, Hannah Mitterwallner, Jonathan Penca, Maria VMier

15.12. 2023 – 18.02.2024

Lothringer Halle, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

Texts included in the exhibition:

MUNICH

15.12. 2023 – 18.02.2024

Lothringer Halle, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

Texts included in the exhibition:

7.01.2024, 3 pm

Lothringer 13 Lokal

Hey, make sure you do not miss Tim Barker talking with me tomorrow, Sunday the 7th at 3 pm at Lothringer 13 Lokal! Really interesting way of looking at now technology affects our experiences of time! Part of the current “From Animal to Mineral Exhibition”.

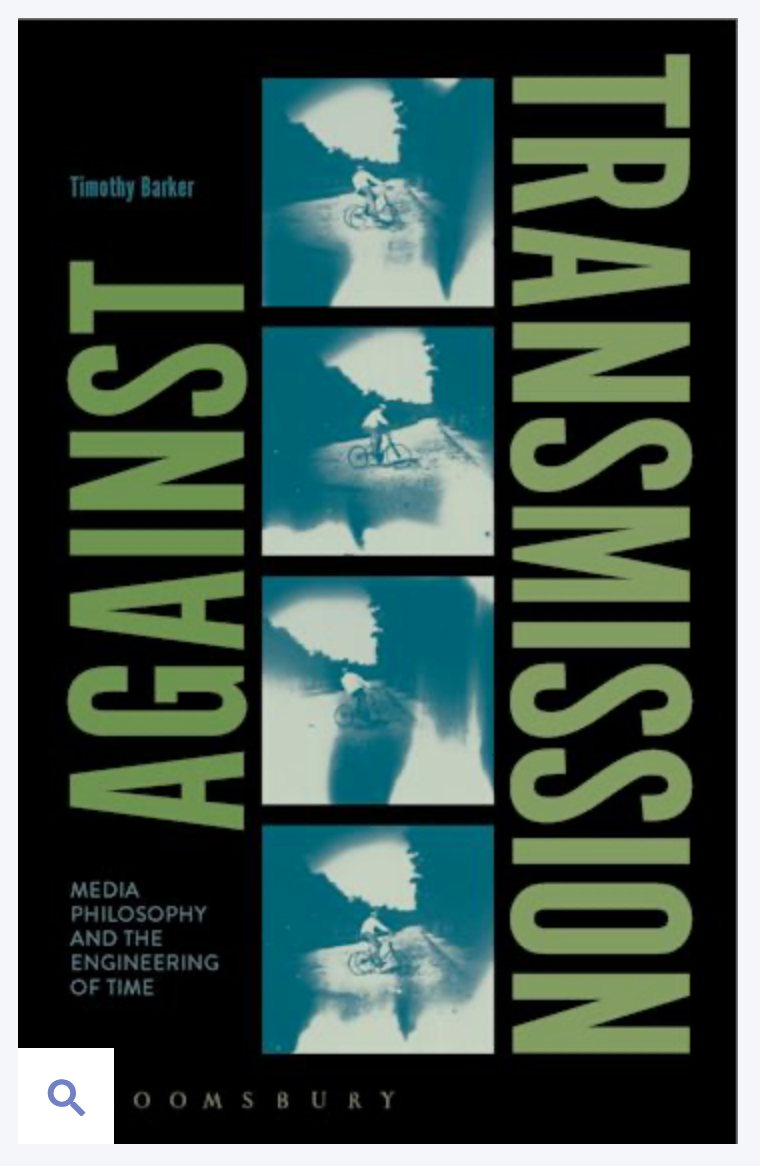

Tim Barker is Professor of Media Technology and Aesthetics at the School of Culture & Creative Arts, University of Glasgow. Tim’s research interests include digital technology and new media, aesthetics and the philosophy of time. He is the author of Time and the Digital: Connecting Technology, Aesthetics, and a Process Philosophy of Time (2012) and Against Transmission: Media Philosophy and the Engineering of Time (2018) and numerous articles including the most recent “Unplayable games: time and digital culture” Kunsttexte (2023); “Michel Serres and the philosophy of technology” Theory, Culture and Society (2023), “Michel Serres’ messengers” Media Theory (2021) and “Between emergence and emergencies: an introduction to the special issue ‘Media, Materiality, and Emergency’” MAST: The Journal of Media Art Study and Theory (2020).

One of the concepts of the exhibition From Animal to Mineral is the radical openness of Deleuze and Guattari’s becoming “tout le mode,” like everybody, like the whole world. In his short talk Tim Barker will introduce the concept of “totipotence” as discussed in the philosophy of Michel Serres, biologically defining the ability of a cell to give rise to unlike cells and so to develop a new organism. Serres uses this idea to discuss technological and cultural developments in evolutionary terms.

15.12. 2023 – 18.02.2024

Lothringer Halle, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

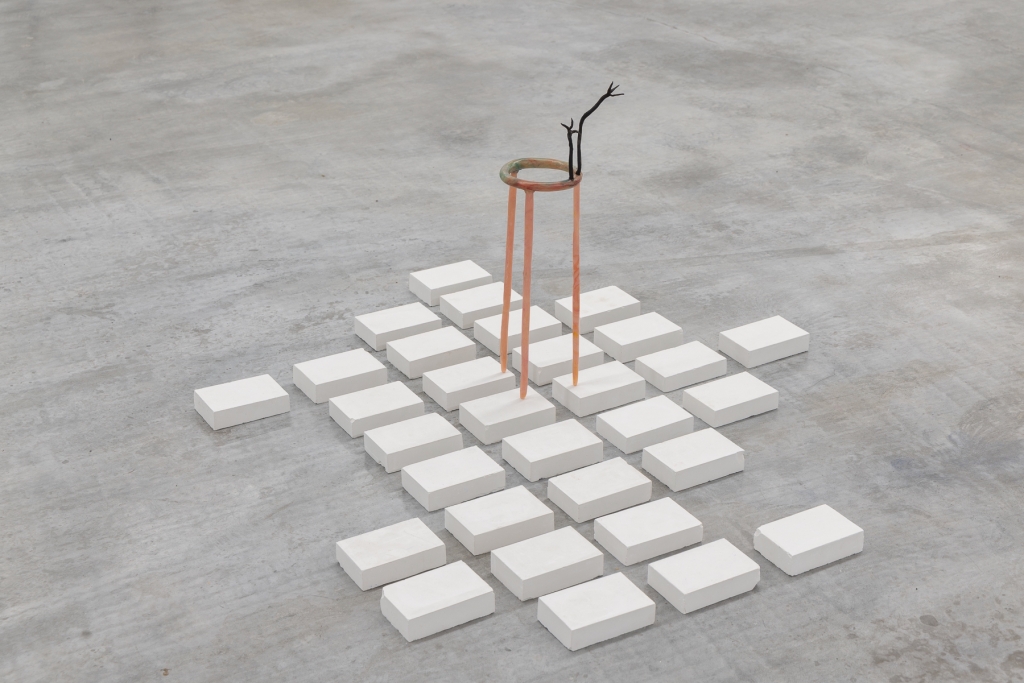

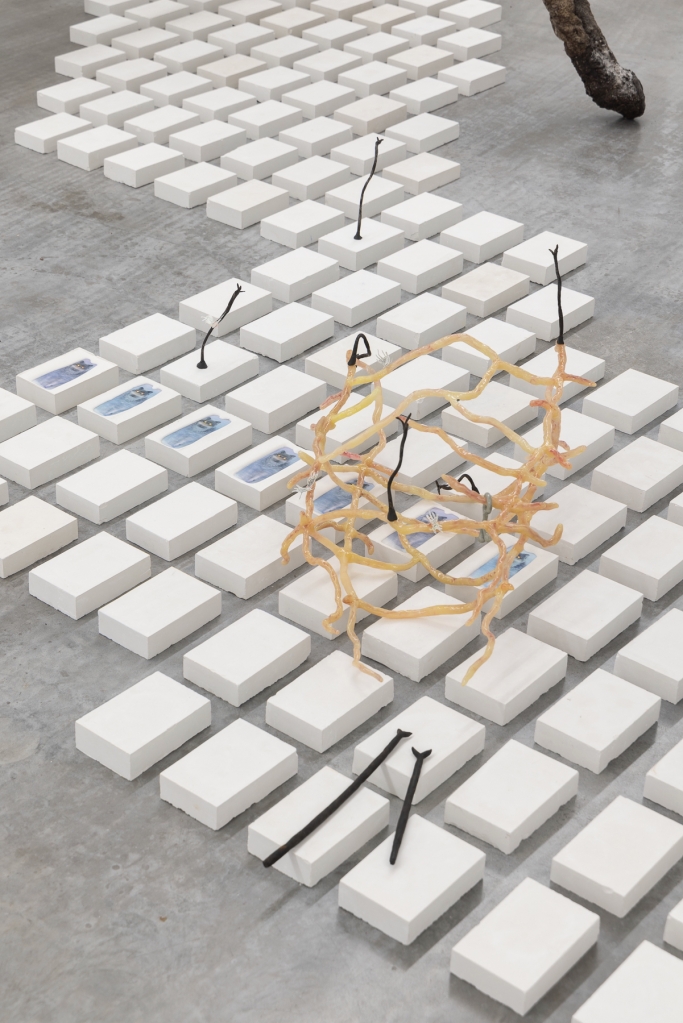

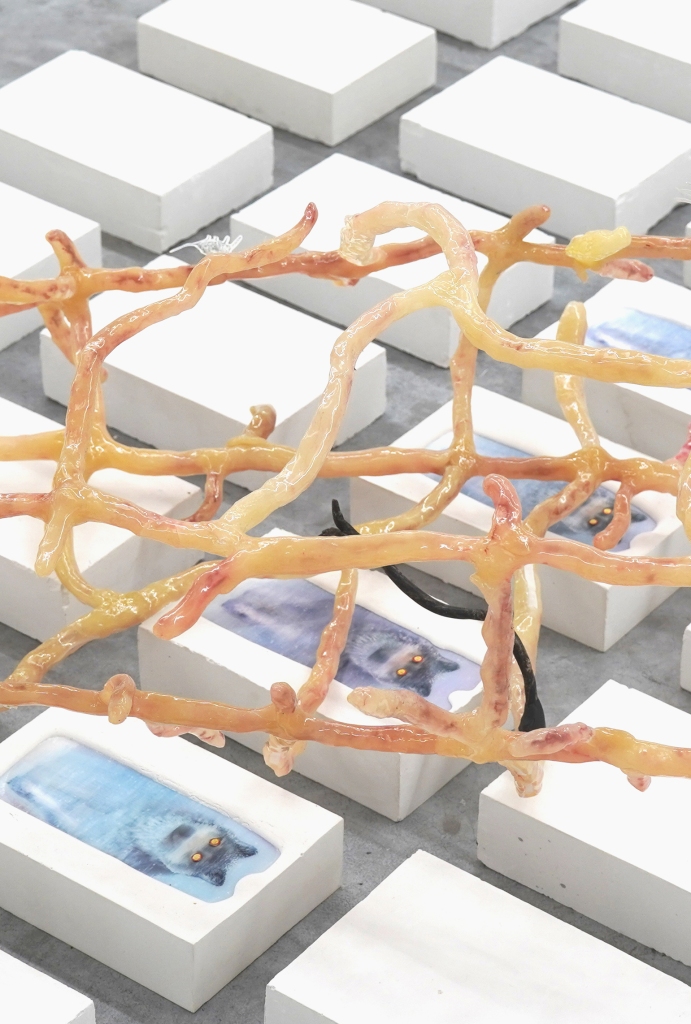

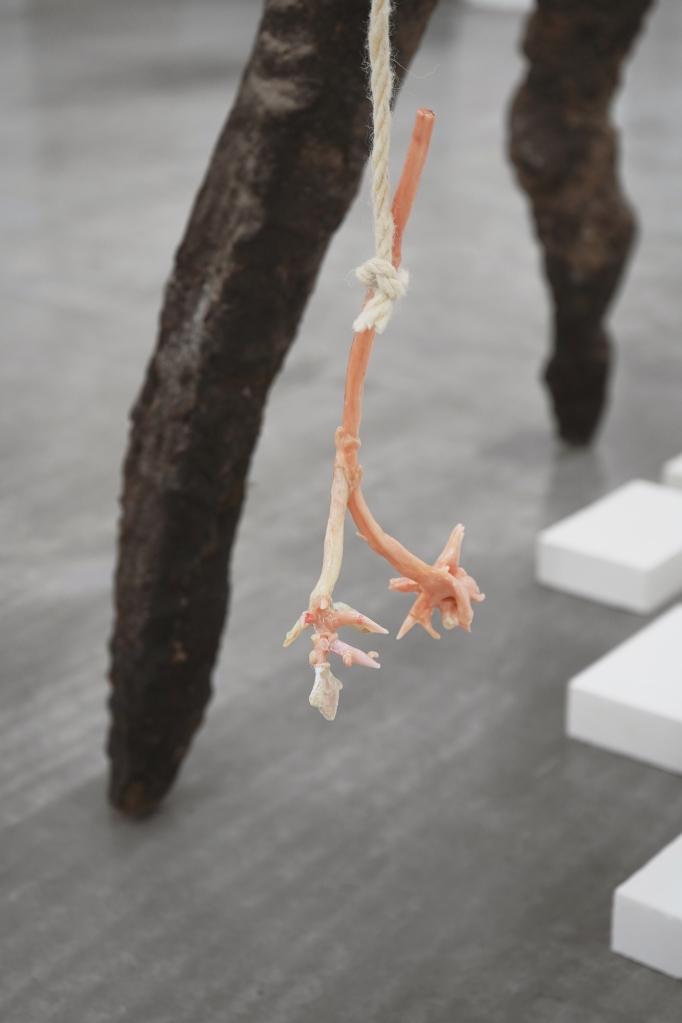

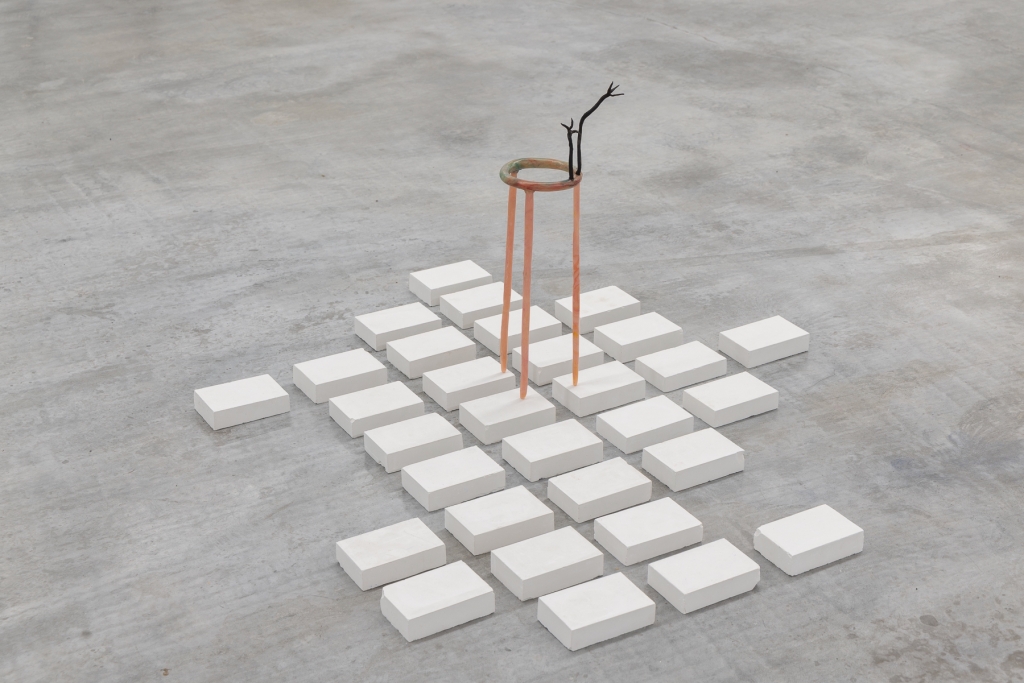

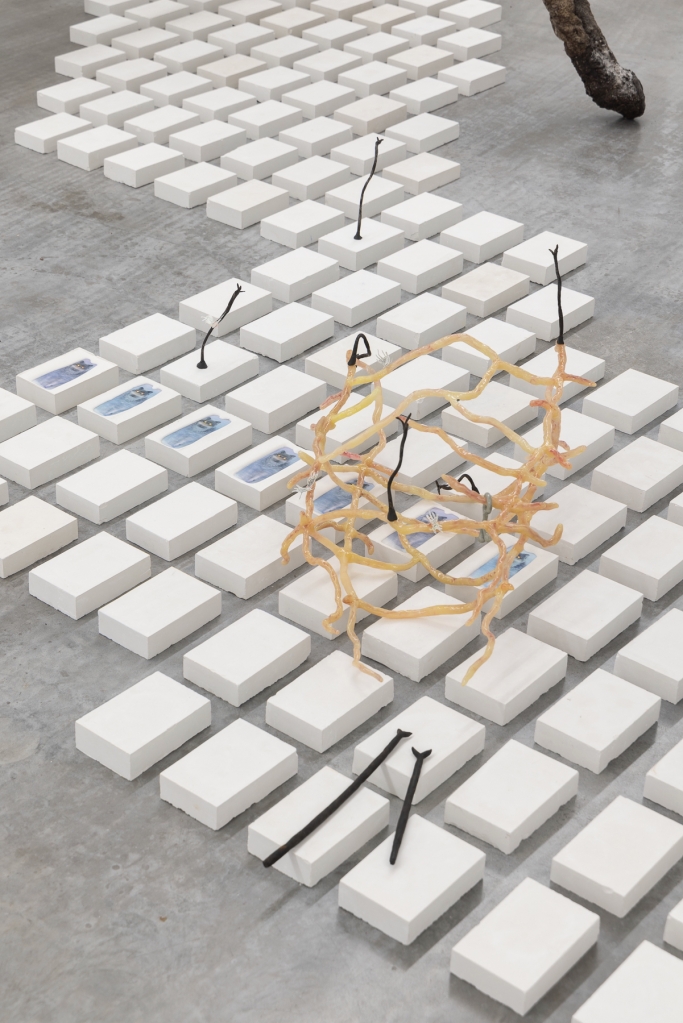

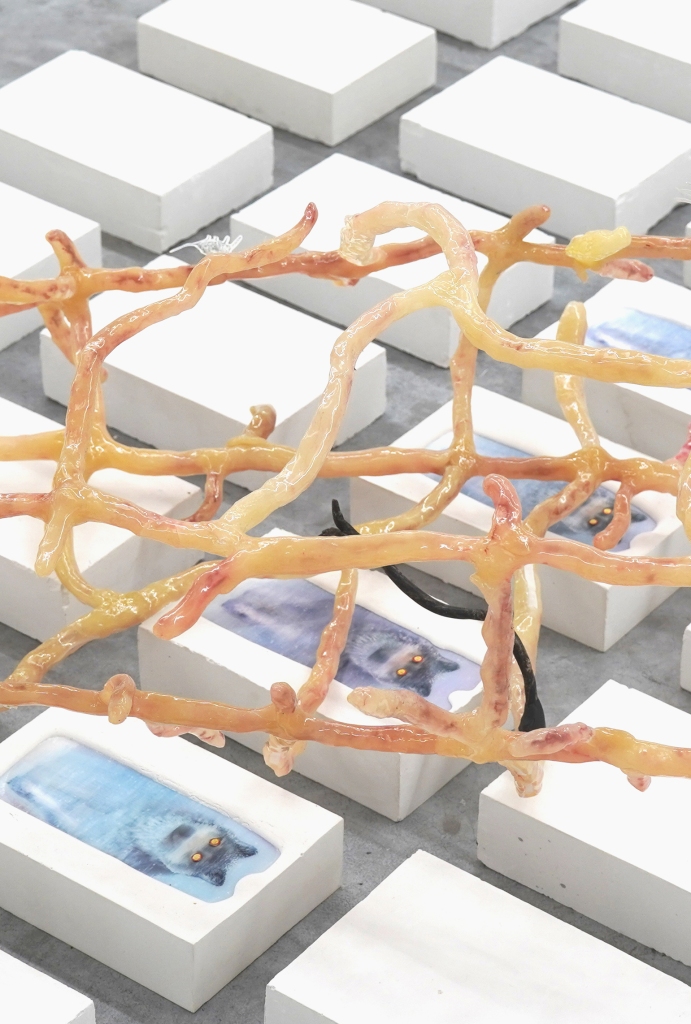

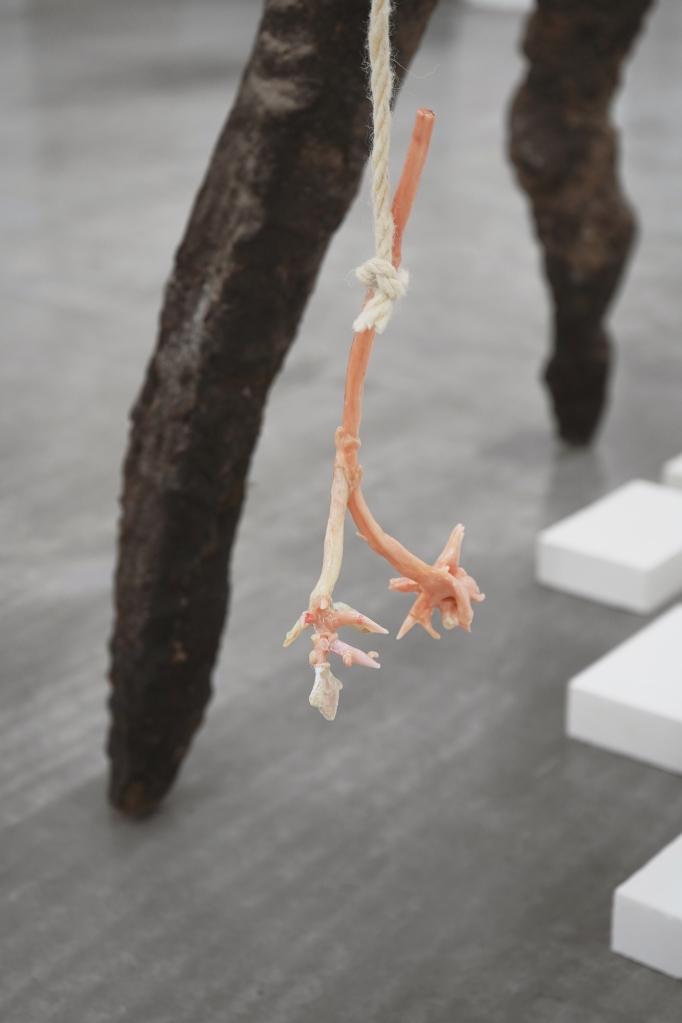

“Animals” are wolves mainly, rats and the wasp. “Mineral” is everything imperceptible: elements, particles and molecules. To go from animal to mineral is to experience becoming, to step across a threshold and change.

I began my reading of A Thousand Plateaus, specifically the chapter “1730: Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming- Imperceptible …” 1 during the corona pandemic, when environmental concerns were at the forefront of almost every media discussion. Defining humanity’s role in nature seemed like an important task and Deleuze and Guattari’s work was useful in addressing the too easy distinction between nature and culture. I liked how Deleuze and Guattari saw the dominance of our species over others as a philosophical problem of autonomy where Man as a thinking being is subject only to the laws of his own construction. For them, the capacity for conscious thought conferred upon Man a dignity denied to other creatures, making their voices unheard.

Whereas, in A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari present nature as an endless variability, the “whole thousand-voiced multiple” of Difference and Repetition 2. Here, nature is a multi-voiced body, where the voices constituting this body resound in each other in a “clamor of Being.” In this din, my voice is one of many and many voices resonate in mine 3. For Deleuze and Guattari, to change the human collective relation, not just to animals, but to earth itself, would demand that we stop hearing just our own voice and become aware of the noise of others. This is the experience of becoming-animal, becoming-imperceptible. It is to shed Man’s mantle and learn how to listen, becoming the voice of many.

Since 2021 I have realised a series of exhibitions at various locations in responses to different aspects of this chapter of A Thousand Plateaus, whether to its ideas of nature, technology or memory. This exhibition at Lothringer 13 Halle confronts the idea of becoming, specifically in our relation to nature, more directly. In different ways all the artists participating in this exhibition share these concerns, many acutely aware of working in the era of the Anthropocene, where the human impact on the planet can no longer be denied.

To their cluster of voices I add my own, belonging to the writer. The texts I have written over the past few years in response to Deleuze and Guattari’s chapter on becoming are on display throughout the room. The texts resonate with the artwork, and the art inhabits the text. The exhibition is an experiment in the construction of a multi-voiced population, a pack of wolves, a people of rats.

Magdalena Wisniowska, November 2023

1) Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi, (Minneapolis, London: University of Minesota Press, 2005).

2) Deleuze, Gilles, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 304.

3) Ibid.

07.09. – 12.11.2023

Lothringer 13 Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

It begins with the amoeba, like the one we drew at school: flower-like, dotted with vacuoles, a circular nucleus in the middle. An amoeba, despite not having a brain, a nervous system or indeed any kind of sensory cells, can react. It moves around the murky pond water that makes up its environment, finding food, avoiding predators, anticipating, reacting. It has no need for organs. Organs developed later, in the course of evolution, as a means fulfilling functions to a higher degree. An organism with a brain, can think better than an organism without one.

French philosopher Raymond Ruyer considers all organs to be technical artefacts, technologies developed by the organism as it evolved. By having a brain and a nervous system, we have access to technologies an amoeba doesn’t have and this makes us feel sophisticated. We can make complex decisions, solve problems and form concepts, leaving murky pond water behind.

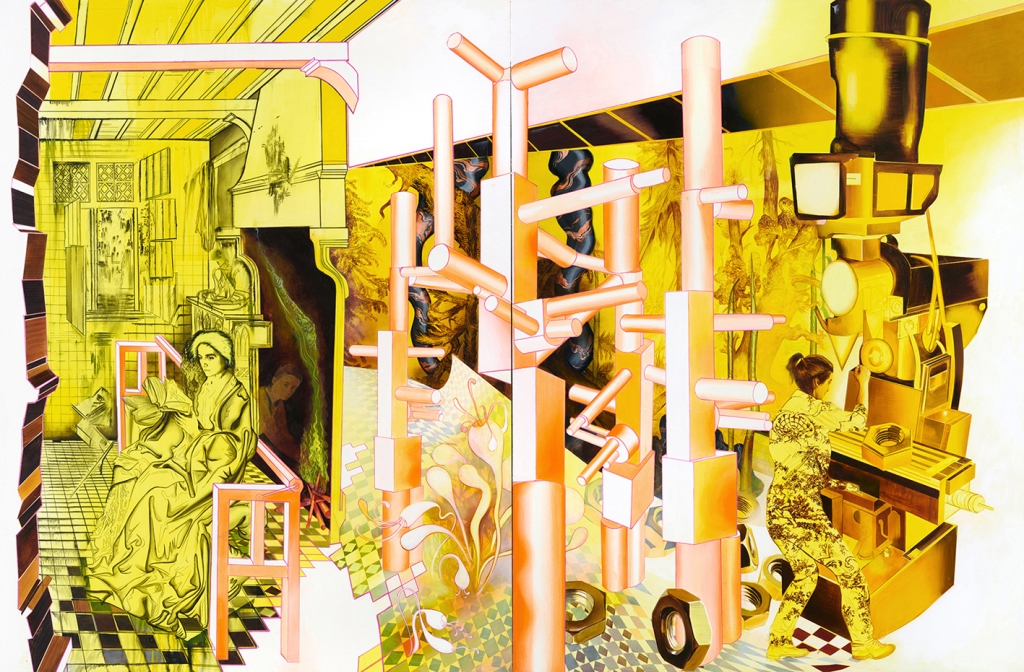

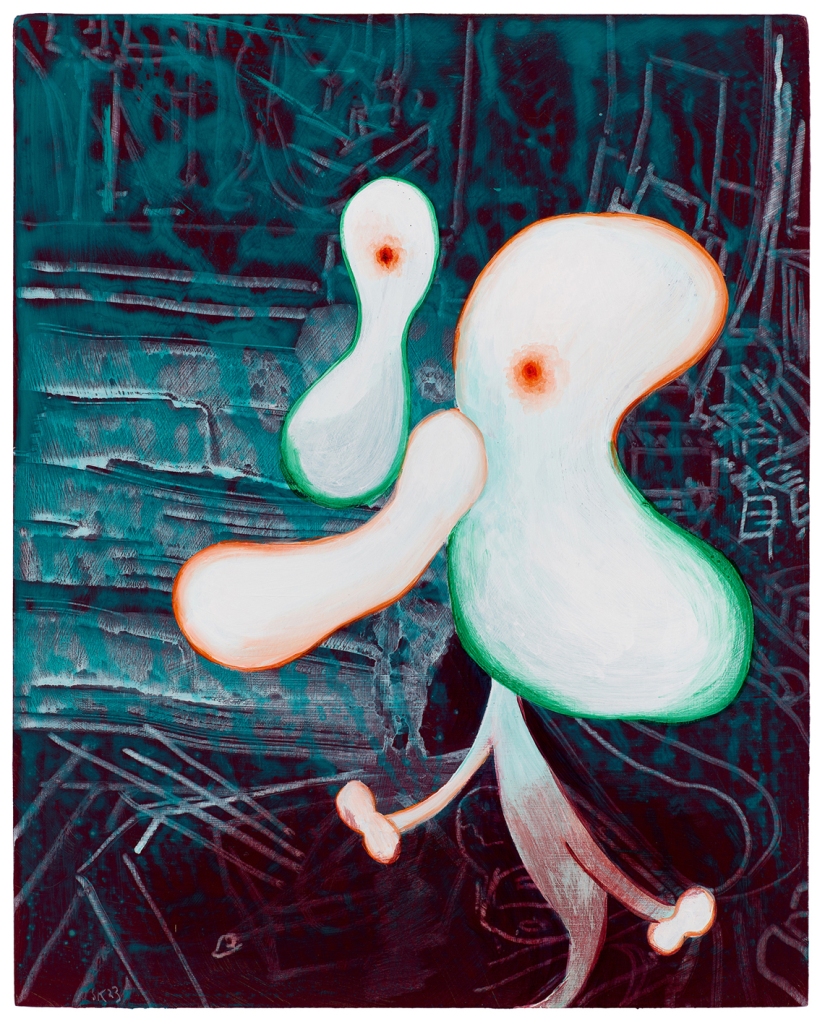

Like in Susanne Kühn’s paintings, there is no line between the artificial and the nature. If the organ is a technical artefact, it does not differ from the other artefacts, those tools and machines that we surround ourselves with. The organ belongs to an internal proto-technicity, while the machine is the externalised projection of the organ. Each also has its own evolutionary trajectory, one internal, the other external, an exo-darwinism.

In the painting “Robota I” we see the artist in three different guises: as St. Barbara reading, as a young woman in East Germany working, and as a mother tending the fireplace. Three technologies are depicted here, all extensions of the body. There is the book, the pool of knowledge, acting as an extension of the brain. Tools and machines such as found in a factory are extensions of the human hand. Fire, to keep us warm and to heat up food, is the most primitive of technologies, an extension of our thermoregulation and digestive system. Working with these technologies makes up the life of the artist.

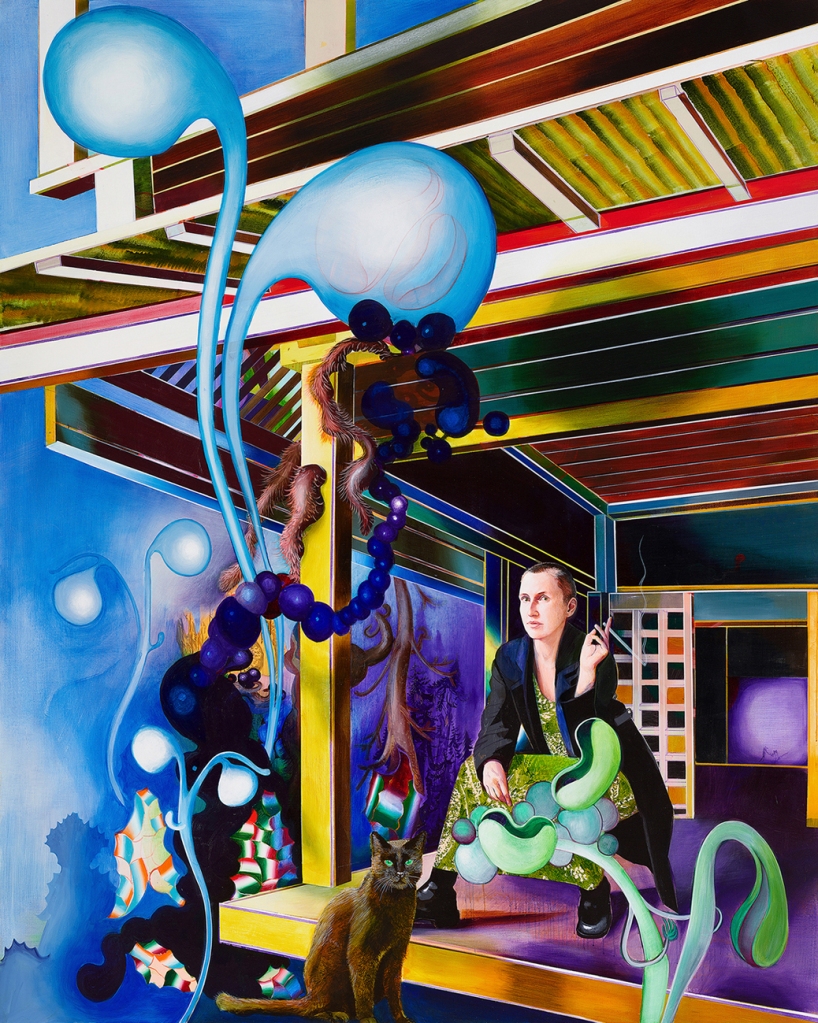

Similarly, the biological has a technological aspect in “Her name is Amygdala Vertigo.” The reference is to the amygdalae, two bean-shaped clusters of deep within the cerebrum of the brain, which we learn are responsible for memory, decision making and emotional response. Diagrammatically, they look like the EarPods which seem to sprout out of the picture frame, softly-curved and convex. They are surrounded by the sharp, multicoloured concave curves of the hand ax, one of the first man-made tools. The portrait is of an extended body, spread over various technologies depicted on the canvas.Foremost, Susanne Kühn is interested in those moments in which the forward pushing trajectory of evolution and technological development foams up in bubbles of effervescence. Her painting is not of lines which separate, marked by horizontal and vertical coordinates – the sharp perspective she often uses, stutters quickly in her work. Hers are lines without connecting points.

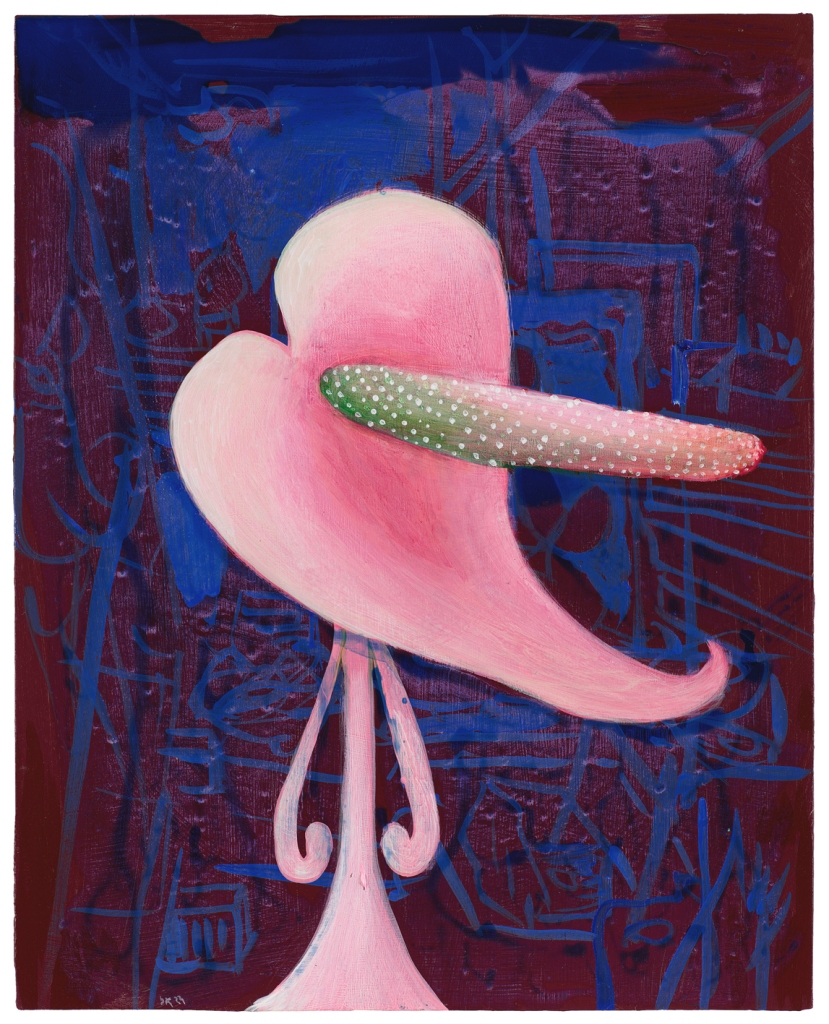

“Frauenschuh – Lady’s slipper” is a self-portrait, the mess of detritus standing in for the technologically extended body: we see a smartphone, medication for the menopause, a sneaker, toothpaste. The flower itself is a cultivated hybrid, its natural evolution determined by man. In this work, the extended body of man, is also a body outside of the dictates of evolution, a “deterritorialised” body no longer adapted to any particular environment. A “deterritorialised” hand is nothing more than a useless pink cartoon blob. It ends with the amoeba in the pond, the water now an acid yellow, surrounded by toxic corals and water plants.

Magdalena Wisniowska 2023

Es begann mit der Amöbe, wie wir sie in der Schule gezeichnet haben: blütenförmig, mit Vakuolen übersät, mit einem kreisförmigen Zellkern in der Mitte. Obwohl die Amöbe weder ein Gehirn, noch ein Nervensystem oder Sinneszellen hat, besitzt sie die Fähigkeit auf ihre Umgebung zu reagieren. Auf der Suche nach Nahrung bewegt sie sich im trüben Teichwasser, weicht Fressfeinden aus, antizipiert und reagiert. Dafür braucht sie keine Organe, denn erst im Laufe der Evolution entwickeln sich diese, um komplexere Funktionen erfüllen zu können. Ein Organismus mit einem Gehirn kann besser denken als ein Organismus ohne Gehirn.

Für den französischen Philosophen Raymond Ruyer sind alle Organe technische Artefakte; Technologien, die der Organismus mit der Zeit entwickelt hat. Im Gegensatz zur Amöbe haben wir durch unser menschliches Gehirn und unser Nervensystem Zugang zu diesen Technologien. Das gibt uns das Gefühl, hoch entwickelt zu sein. Wir sind in der Lage, komplexe Entscheidungen zu treffen, Probleme zu lösen und Konzepte zu entwickeln, und lassen dabei das trübe Teichwasser hinter uns.

In den Gemälden von Susanne Kühn gibt es keine Grenze zwischen dem Künstlichen und der Natur. Ist das Organ ein technisches Artefakt, unterscheidet es sich nicht von den anderen Artefakten; den Werkzeugen und Maschinen, mit denen wir uns umgeben. Das Organ gehört zu einer inneren Proto-Technizität, während die Maschine die externe Projektion des Organs ist. Beide haben zudem ihre eigene evolutionäre Entwicklung, die eine intern, die andere extern, ein Exo-Darwinismus.

Im Gemälde “Robota I” sehen wir die Künstlerin in drei verschiedenen Gestalten: als lesende Heilige Barbara, als junge Frau in Ostdeutschland bei der Arbeit und als Mutter, die das Feuer anfacht. Drei Technologien werden hier dargestellt, allesamt Erweiterungen des Körpers. Da ist das Buch: der Wissensspeicher, der als Erweiterung des Gehirns fungiert. Werkzeuge und Maschinen sind Erweiterungen der menschlichen Hand. Mit dem Feuermachen wärmen wir uns und bereiten Nahrung zu. Es ist die primitivste aller Techniken, sie ist eine Erweiterung unseres Thermoregulations- und Verdauungssystems. Die Arbeit mit diesen Technologien bildet das Schaffen der Künstlerin.

In ähnlicher Weise hat das Biologische einen technischen Aspekt in “Her name is Amygdala Vertigo”. Im menschlichen Gehirn besteht die Amygdala aus zwei tiefsitzenden mandelförmigen Zellstrukturen, die, wie wir lernen, für Gedächtnis, Entscheidungsfindung und emotionale Reaktionen zuständig sind. Schematisch gesehen gleichen sie den EarPods, die aus dem Gemälde herauszuwachsen scheinen, sanft gebogen und konvex. Sie sind umgeben von den scharfen, vielfarbig konkaven Kanten des Faustkeils, einem der ersten vom Menschen hergestellten Werkzeuge. Das Porträt, als „extended body“, beinhaltet die auf der Leinwand dargestellten Technologien.

Susanne Kühn interessiert sich vor allem für jene Momente, in denen das Fortschreiten der Evolution und der technologischen Entwicklung aufschäumen. Die klaren Linien ihrer Malerei entstammen keinem präzisen Koordinatensystem, vielmehr zerbricht das perspektivische Konstrukt des Bildes schnell. Ihren Linien fehlen die Verbindungspunkte.

“Frauenschuh” ist ein Selbstporträt, in dem die Ansammlung von nicht abbaubarem Müll für den technologisch erweiterten Körper steht: Wir sehen ein Smartphone, Medikamente für die Wechseljahre, einen Turnschuh, Zahnpasta. Die Blume selbst ist eine gezüchtete Hybride, deren natürliche Entwicklung vom Menschen bestimmt wurde. In diesem Gemälde ist der erweiterte Körper des Menschen auch ein Körper außerhalb des Diktats der Evolution, ein “deterritorialisierter” Körper, der nicht mehr an eine bestimmte Umgebung angepasst ist. Eine „deterritorialisierte“ Hand ist nichts weiter als ein nutzloser rosa Cartoon-Klecks.

Es endet mit der Amöbe im Teich, dessen Wasser nun säuregelb ist, umgeben von giftigen Korallen und Wasserpflanzen.

13.07. – 20.08.2023

Lothringer 13 Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

At each corner, each fork in the road, we encounter the same: Man. Not some man, a particular man with a friendly, if white European face, but man as a standard on which every opposition is based. This is the man that is the principle term in the opposition of male/female, white/red, rational/mad. A center point from which all other points take measure. The point of origin all other points echo. This kind of man is one “gigantic memory.”

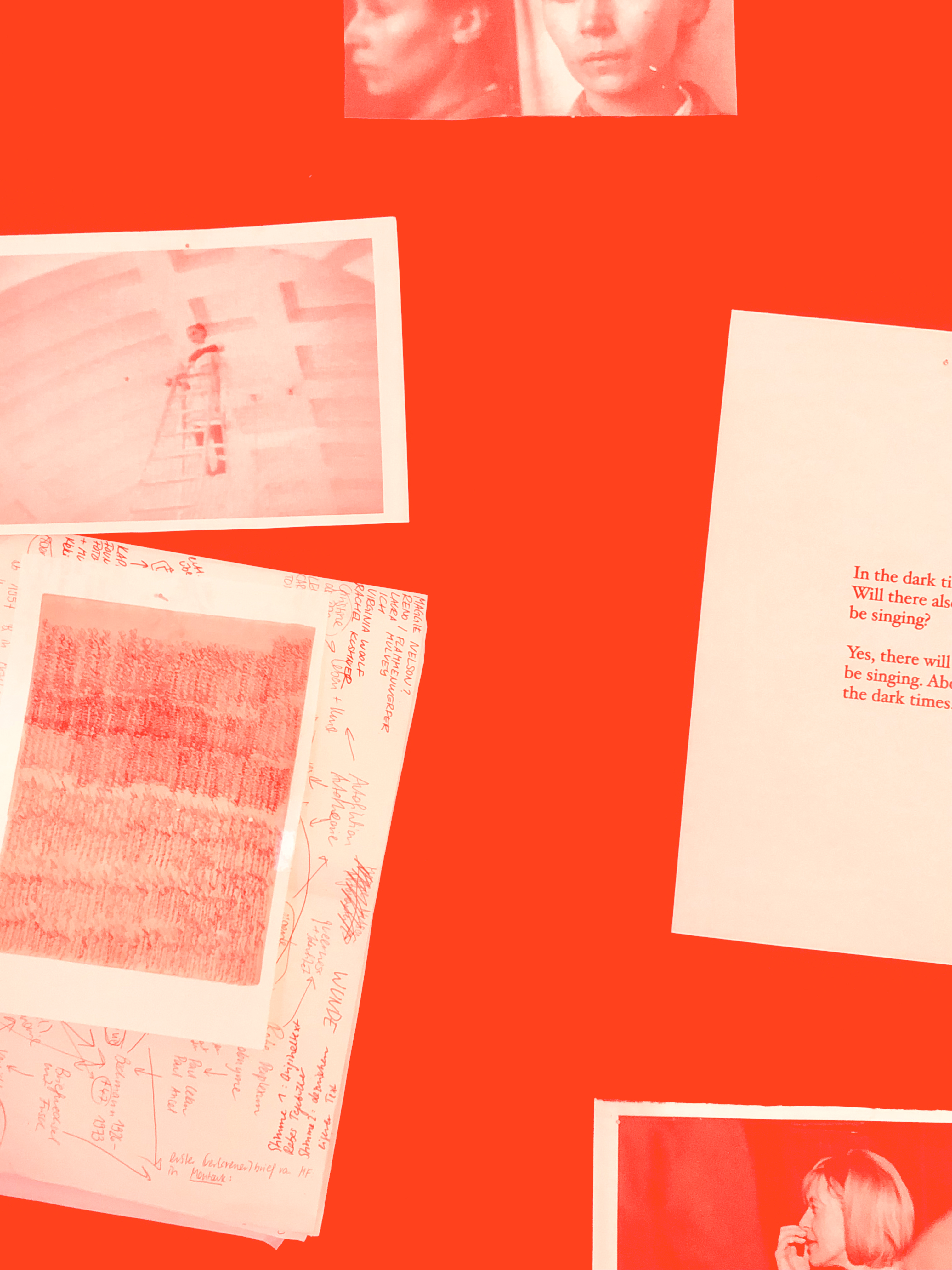

The path we take instead is a straight one, without any crossroads. As soon as we open the door to the Lothringer 13 Studio space there is only the left. Nothing takes place on the right hand side. On the left there are four large windows covered with transparent red filter and once again there is no alternative to the redness that saturates the entire room with colour. Also on the left there are three deck chairs clustered around some speakers. Left is an open window. A poster hangs at the very edge of the distant wall behind.

At each step of the exhibition “The Flamekeepers” Lilian Robl invites us to think of lines. In this sound sketch that is part of the preparation work for a larger video piece, the protagonists – Emma Hauck, Ingeborg Bachmann, Rabe Perplexum – are not points but lines. For points would be women who as minorities are defined in opposition to the major term, man. Whereas lines flicker with flames of becoming. The lines of becoming are not the mathematical lines of history connecting two or more distant events in the point system of memory. Rather these lines pass between points, constituting a distinct no-man’s land. On this land no man can stand, because here is a place where the discernibility of points disappears. Deleuze and Guattari write that these murky zones form a “line-system of becoming.”

Robl is very good at identifying these indiscernible points, these lines of becoming, in order to constitute a kind of anti-archive, a non-collection of anti-memories. There is Emma Hauck, who in her schizophrenia feels she can control her world and make a nurse jump or a housefly drown. She sits down to repeatedly write to her husband: komm! Her writing is her body as she mechanically writes and rewrites the same word. Her writing is also a landscape she sees out of her window, a grey forest of lines you can walk into. Recalling Heathcliff’s wish to embrace Catherine’s corpse, Ingeborg Bachmann writes of wanting to embrace the skeleton of her lover, filling her decayed mouth and choking on the with the dust he has become, at one with his nothingness. Rabe Perplexum changes their name by deed poll to become-raven, flying about and causing havoc from Gärtnerplatz to Stachus.

Their’s is a terrible suffering. Emma Hauck dies in the Wiesloch asylum, without ever seeing her husband or daughters again. While high on drugs, Ingeborg Bachmann accidentally sets herself alight and dies from her injuries. Rabe’s tongue is a knife and they commit suicide after alienating their friends. To walk in straight lines and not remember – not to make memories by not connecting the distant points of historical events – is painful. But pain and suffering is also what brings about proximity. We are close to them in their suffering because we no longer separate entities but participants in becoming. When there are no binary distinction at play, they can affect us still and something of theirs passes to us. The wound for Robl must continually be licked open.

Magdalena Wisniowska 2023

13.07. – 20.08.2023

Lothringer Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

Emma Hauck. Ingeborg Bachmann. Rabe Perplexum. Not points but lines. Lines which do not connect points but travel swiftly in between. The archive, history, memory are collections of points tied to one central point: Man, defined as white, male and rational. In her exhibition with GiG Munich, “The Flamekeepers” Lilian Robl seeks ways of remembering without memory, recording without constructing an archive. Just lines. Only lines.

Lilian Robl (*1990) studied Fine Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich and at the Ecole de recherche graphique, Brussels, graduating as a master student of Prof. Alexandra Bircken in 2019. Her work was shown in numerous exhibitions: Top Space, Berlin (DE); Kunstraum Kreuzberg, Berlin (DE); fructa, Munich (DE); Wienwoche (AT); Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich (CH); Kunstverein Marburg (DE) as well as at film festivals: Les Instants Vidéo, Marseille (FR); Barcelona International Short Film Festival (ES); GRRL Haus Cinema, Berlin (DE); FILE, São Paulo (BR); Women’s Voices Now, Los Angeles (US); Non- syntax, Tokyo (JP); International Moving Film Festival (IR); Light Mattter Film Festival (US). She has received residencies at the Cité Paris (FR), among others.

Emma Hauck. Ingeborg Bachmann. Rabe Perplexum. Nicht Punkte, sondern Linien. Linien, die keine Punkte verbinden, sondern sich schnell dazwischen bewegen. Das Archiv, die Geschichte, die Erinnerung sind Ansammlungen von Punkten, die mit einem zentralen Punkt verbunden sind: Der Mensch, definiert als weiß, männlich und rational. In ihrer Ausstellung “The Flamekeepers” im GiG Munich sucht Lilian Robl nach Wegen des Erinnerns ohne Gedächtnis, des Aufzeichnens ohne Aufbau eines Archivs. Gerechte Linien. Nur Linien.

Lilian Robl (*1990) hat Freie Kunst an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste München und an der Ecole de Recherche graphique Brüssel studiert und 2019 als Meisterschülerin von Prof. Alexandra Bircken abgeschlossen. Ihre Arbeiten werden in Ausstellungen, z.B. Top Space, Berlin (DE); Kunstraum Kreuzberg, Berlin (DE); fructa, München (DE); Wienwoche (AT); Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich (CH) sowie auf Filmfestivals, z.B. Les Instants Vidéo, Marseille (FR); Barcelona International Short Film Festival (ES); GRRL Haus Cinema, Berlin (DE); FILE, São Paulo (BR); Women’s Voices Now, Los Angeles (US); Non- syntax, Tokyo (JP); International Moving Film Festival (IR); Light Mattter Film Festival (US). Sie erhielt Residenzstipendien unter anderem an der Cité Paris (FR).

Another studio visit and resulting exhibition text:

I owe you the truth in painting and I will give it to you

Cézanne

…d’un seul pas franchi…

Derrida

The small problem of truth has been occupying me recently: the truth in painting, as promised by another “sauvage raffiné,” Paul Cézanne. A long time ago, it took a painting by Vincent van Gogh, Old Shoes with Laces (1886), for the German philosopher Martin Heidegger to recognise what this truth might be and for him, the artwork became defined through its revelation of this truth. We now consider ourselves too sophisticated to think that a painting of some worn-out shoes reveals something so profound about the peasant woman’s being that there is no other way this can be grasped. And yet a little of this heideggerian desire remains. I find we still look for truth in painting despite thinking it unlikely. Or at least, I do.

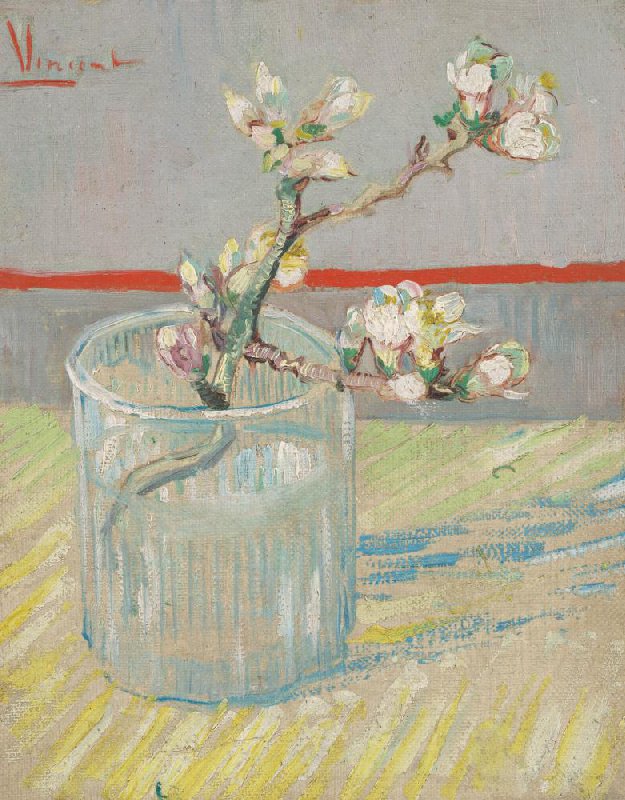

At the height of the pandemic Stefanie Ullmann would walk and run in the rose gardens at the Isar, in May, when the magnolias are in bloom. These caught her attention – I remember how bright that spring was, and how vibrant the greens. But again it took a painting by van Gogh, this time, Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass (1888) for her to begin painting from memory a series of small canvases with flowers. A second series of watercolours followed. The oil paintings share van Goghs’ shimmering green-yellow palette as well as his strong horizontal and vertical lines.

When I look at these paintings I find myself standing in Heidegger’s shoes. There is a truth in Stefanie Ullmann’s work that has to do with his schematic definition. On the one hand he claims, art has long been thought as formed matter, in other words as a “Zeug,” translated by Derrida as a “product,” more commonly in English translations of Heidegger’s essay as “equipment.” And these paintings here, especially the abstract ones, have this workman-like quality of being built, almost brick by brick, layer by layer. Occasionally Stefanie Ullmann even uses a spatula like a masonry trowel. And yet, as Derrida in his interpretation of Heidegger’s argument rightly notes, an artwork is more than a product or Zeug because it does what no other product can – it resembles a thing, “Ding.” It is as if it were not produced. Thus, an artwork is a product that is also more than a product, because it crosses over, steps into the realm of the thing. In the same way, Ullmann’s paintings enjoy this self-sufficiency. Despite their lightness, they feel as sturdy as earth or rock or tree, untouched by human hand.

The point of painting is – for Van Gogh, Heidegger, Derrida etc. – that this step crossing from thing to product and back again occurs within. Painting shows how tightly things, Zeug and artworks interlace.

23.03. – 26.05.2023

Lothringer 13 Studio

Photos: Lukas Hoffmann

What is the truth?1 Now there is a metaphysical question for you. Hardcore baby, yeah. That’s what we are talking about. What. Is. The. Truth. Heidegger turns around and points, there – there – to the temple, a Greek one I guess but no one really knows, or cares, as it really doesn’t matter; he points to the temple nestling among rocky hills, its columns in picturesque disarray. We can see it on Paul Valentin’s holiday snapshot. The temple as a work of art sets forth the truth. If you are looking for the truth you can find it there.

When I first encountered Heidegger’s essay as an undergraduate, “The Origin of the Work of Art” was presented to me as a critique of representation, specifically of mimesis. I admit I didn’t get it at the time. Now that I do, Heidegger does clearly state that the kind of truth he associates with the artwork has nothing to do with a painter’s capacity to produce resemblance. Truth here is not marked by the distinction between the model and the copy, the original and the fake, and in this sense his argument is anti-mimetic. Instead, he looks to the point of origin of the art work, and finds truth (with the help of van Gogh’s painting) in the way being is revealed. “Aletheia”, he claims, is the Greek term for the “unconcealedness of beings.”

This means we do not look at an artwork in a habitual way, as a thing or a piece of equipment. Heidegger rejects the interpretation of the artwork as either a substrate bearing traits, a manifold of sensations or as formed matter. These for him are various forms of assault on being. He argues that not to fall under the spell of this violence, we have to look at the temple and see how it both creates a world for us, in the sense of giving our lives its meaning, and also shelters this world by placing it back firmly on the earth, which only through the creation of this world emerges as ground. The temple as the work of art is Aletheia.

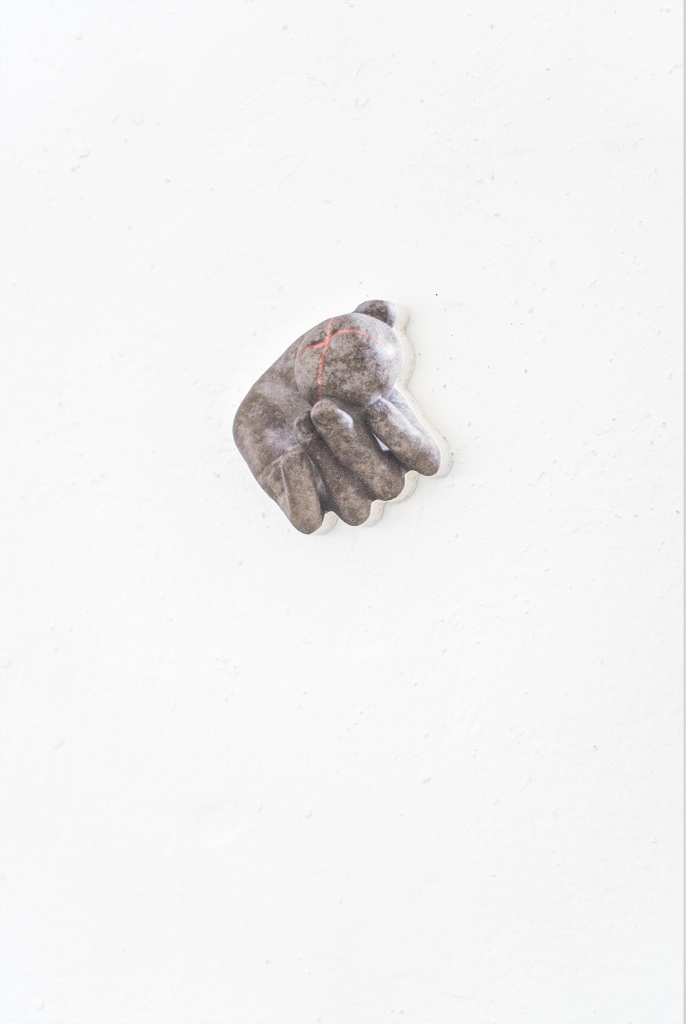

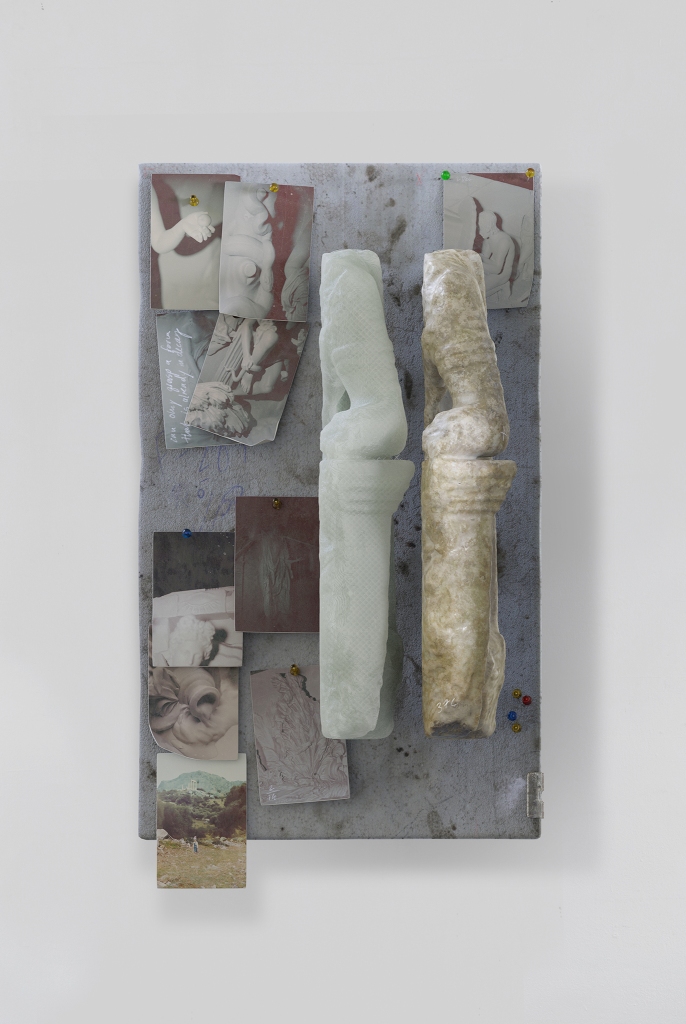

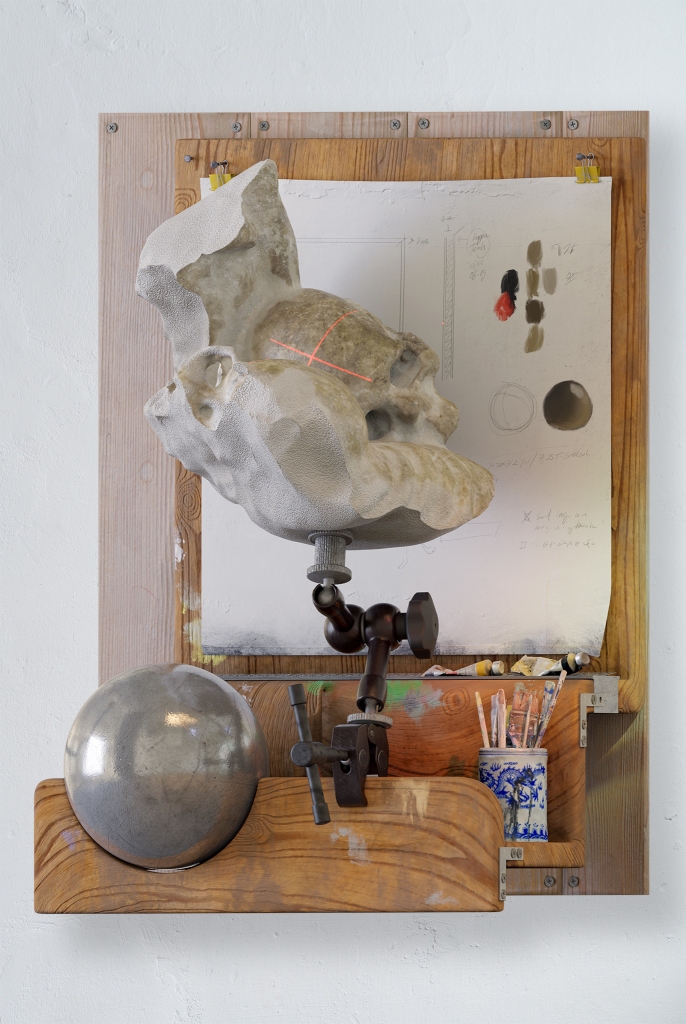

Paul Valentin creates his temple of of the Greek goddess Aletheia using digital software. It has the usual pediments and carved reliefs of mythological figures. He then, also digitally, breaks this temple up, fragments it, ages it artificially and destroys it. He takes up these fragments – still digitally – and reassembles them in workshop that shares many of the same visual conditions as the Lothringer 13 Studio space, like some kind of virtual archeologist. The reassembled fragments are photographed, printed and scattered across gallery room.

Thus there is no truth in Paul Valentin’s temple. Even the snapshot we see is a composite of an old photograph and an ai generated image, with some photoshopping in between. His temple does not, cannot, reveal anything. It is not even there. And yet it shows how mimesis is always at work, even in Heidegger’s argument. How does Heidegger reject the three modes in which we tend to think the artwork? By looking at how their claim to truth compares with the artwork’s truth, its revelation of being. Isn’t this also what mimesis is? I mean, isn’t the relation between a model and a copy not so much about resemblance as it is about good and bad resemblance – to what extent is the copy a faithful one? Isn’t it the copy’s claim to truth that we compare? Far then from producing a critique of representation, Heidegger’s comparison of different modes of thought would seem to fall down mimesis’s slippery slope. He too succumbs to its power. What is the truth? There is no truth, honey. Only simulacra. Paul Valentin shows that the question we need to ask is how does this simulacra work.

Magdalena Wisniowska 2023

23.03. – 26.05.2023

GiG Munich is really happy to continue working with Lothringer 13 again this year, and will begin the new series of exhibitions – Thought in Practice – at the Studio space with the exhibition “Doxa,” by Paul Valentin. The series aims to bring together different artists, who share a strong interest in philosophical concepts and who make these concepts the focus of their artistic practice.

Paul Valentin’s work has long dealt with the questions of metaphysics, such as the concept of truth, nothingness, or the structure of reality. Similarly in this Lothringer exhibition, “doxa” refers to the Ancient Greek definition of opinion, opposed to the much more serious and worthy “epitome” or knowledge. The exhibition consists of digitally-constructed fictional temple of Aletheia – the Goddess of truth in Greek mythology. Its fragments are not the 3-D artefacts found by archeological teams on a remote site, but the flat illusions, created, artificially aged and distressed by the artist using computer software. In this work Valentin presents truth as something that is always made: fragments of a temple that first had to be constructed before being destroyed.

Paul Valentin is a German artist currently based in Munich, working primarily with video and animation but also occasionally with music, digital relief and sculpture. His work has been presented at the European Media Art Festival, Haus der Kunst, Museum Villa Rot, Centro Cultural Moçambique, Sluice Biennale London and Exchange Rates Festival in New York. He was awarded the Karl & Faber Prize in 2019, as well as the Academy Association Prize that year and the Scholarship for fine arts by the City of Munich in 2021.

GiG Munich setzt auch in diesem Jahr die Zusammenarbeit mit der Lothringer 13 Halle fort. Die neue Ausstellungsreihe “Thought in Practice” startet mit der Ausstellung “Doxa” von Paul Valentin. Ziel der Reihe ist es, verschiedene Künstler:innen zusammenzubringen, die ein starkes Interesse an philosophischen Konzepten haben und diese in den Mittelpunkt ihrer künstlerischen Praxis stellen.

Paul Valentin beschäftigt sich in seinem Werk seit langem mit Fragen der Metaphysik, wie dem Begriff der Wahrheit, dem Nichts oder der Struktur der Wirklichkeit. Entsprechend bezieht sich “Doxa” auf die altgriechische Definition von Meinung in Abgrenzung zu dem viel ernsthafteren und würdigeren “Episteme” oder Wissen. Die Ausstellung besteht aus einem digital konstruierten fiktiven Tempel der Aletheia – der Göttin der Wahrheit in der griechischen Mythologie. Bei den Fragmenten handelt es sich nicht um 3-D-Artefakte, die von archäologischen Teams an einem abgelegenen Ort gefunden wurden, sondern um flache Illusionen, die der Künstler mit Hilfe von Computersoftware geschaffen, künstlich gealtert und verunstaltet hat. In diesem Werk stellt Valentin die Wahrheit als etwas dar, das immer hergestellt wird: Fragmente eines Tempels, der erst gebaut werden musste, bevor er zerstört wurde.

Paul Valentin lebt derzeit in München und arbeitet hauptsächlich mit Video und Animation, gelegentlich aber auch mit Musik, digitalen Reliefen und Skulpturen. Seine Arbeiten wurden auf dem European Media Art Festival, im Haus der Kunst, im Museum Villa Rot, im Centro Cultural Moçambique, auf der Sluice Biennale London und auf dem Exchange Rates Festival in New York präsentiert. Er wurde 2019 mit dem Karl & Faber-Preis ausgezeichnet, ebenso wie mit dem Preis des Akademievereins im selben Jahr und dem Stipendium für Bildende Kunst der Stadt München im Jahr 2021.

25.11 – 30.12.2022

Lothringer 13 Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

I have long, straight hair, slightly dry at the ends, too seldom cut. When I read or write, I tuck the loose strands behind my ear. It is always present, over there, too much to count yet infinitely countable. Oddly, I think of hair when I read Brian Massumi’s definition of the virtual (“Envisioning the Virtual” in The Oxford handbook of Virtuality, 55-70), and not only because of his arguments about value (because you are worth it!). For he opposes the virtual to the actual, rather than the natural or the real, and explains through Whitehead’s opposition of the sensuous and non-sensuous. Hair is sensuous because it exists over there, ready to be counted. There is a reference to space – counting unfolds in time. But hair is also virtual I guess, because it also appears to perception all at once: I do not have to pick a strand and start counting. Hair is there in one fell swoop, or rather swoosh. I already have a rough idea of a number – through habit, previous knowledge and earlier, other experiences. But as soon as I try to locate and fix this dimension – to grasp it in my hand – this virtual aspect disappears into the actual. Massumi describes the non-sensuous as having “a strangely compelling, shimmering sterility” (60) and this makes me think of the hair in this exhibition, Electric bodies shooting through space, silky white curtains on which the video work, Her do, shimmers.

In her work, Janna Jirkova plays with the natural and the artificial. Natural are our bodies: nails, mouth, belly, hair; artificial is the technology, both high and low tech, she attaches to her body in cyborg-like fashion. The electric bodies shooting through space are us, joggers wearing headlights in the dark, Major Tom floating in a tin can. But it is not that technology functions as some sort of extension of our body and its capacities, rather, Jirkova shows how our bodies are already artificial (and by extension, the artificial is already also natural). “Self-prosthetic” is Massumi’s term (64).

The English labels Jirkova reads out in her video, “pretty package… high performance …. the type I like” – but also negatively, “broken … malfunctioning” – are ways to describe both: the human body and technology, the natural and the artificial tangled together in language. On the shimmering screen, we see purple hair being used to tickle a belly, except that the hair is another video projection and the belly, a plaster cast. Again, she touches her navel, but this is on a mobile phone screen, forward facing, in a pouch of a rubber apron, worn over a white protective suit. “Samson, Samson, show me your hair!” Her hair, the hair of the empress Elisabeth. There is body hair shown as a video of a fern unfurling, and the abstract red and pinks are made by placing fingers over the recording device. Jirkova sets out to produce a field of tensions between different modes of existence, actual and virtual. These are tensions that come with the contrast between the sensuous and the non-sensuous. As Massumi argues, modes do not add up to anything – they do not form anything. Experience emerges when the pressure becomes unsustainable and these tensions break (62).

Through this intensive force field all of our experience is conditioned. What we bring to the conditional field phenomenon is our tendencies, in which they are a formative factor. Only these tendencies can be either natural, in the sense of a genetic predisposition or artificial, as in learnt. For Massumi, art and technology merely extend the body’s pre-existing regime of natural and acquired artifice, “already long in active duty in producing the virtual reality of our everyday lives” (64). We are caught between our tendencies in an intensive force field of emergence, indeed like “motes,” “caught up in a tumult of non-Newtonian motion” (Beckett, Murphy, Chapter 6).

Magdalena Wisniowska 2022