Jakob Gilg, Anka Helfertova, Julia Klemm and Jonathan Penca

9.10. – 7.11.2025

with Pracownia Portretu, Łódź, Poland

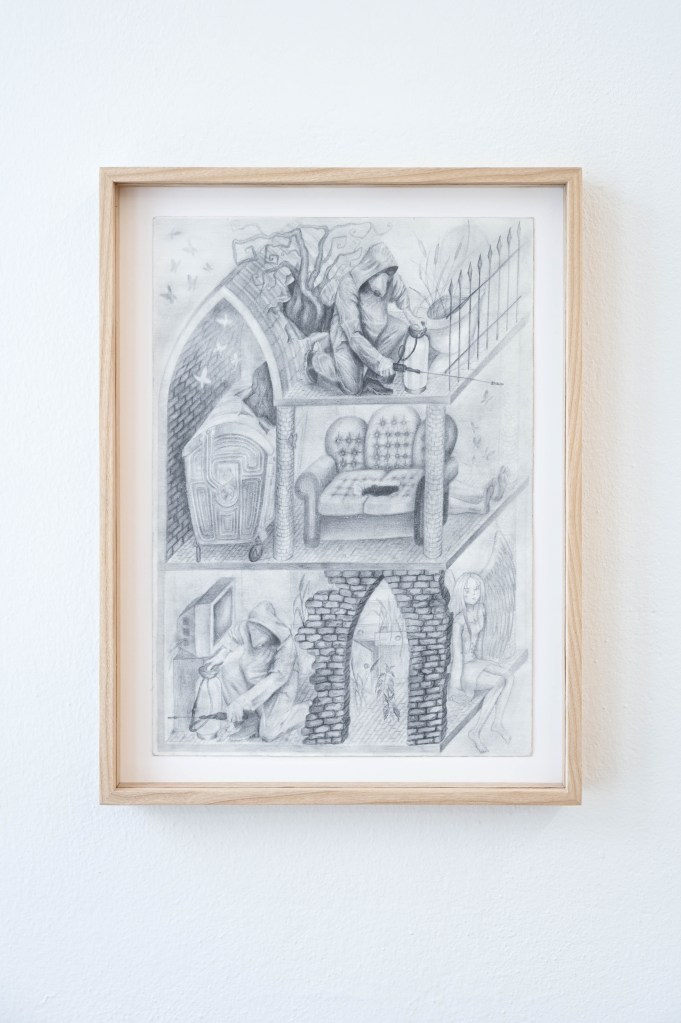

gouache paint, acrylic resin, biro, pencil, gesso and ink on wood. 31 x 24 x 5 cm; Julia Klemm, A chimera is not a pet 2, 2025, steel, glaze, ceramic, pigment, 44 x 38 x 74 cm, )

gouache paint, acrylic resin, biro, pencil, gesso and ink on wood. 31 x 24 x 5 cm, ; Julia Klemm, A chimera is not a pet 2, 2025, steel, glaze, ceramic, pigment, 44 x 38 x 74 cm,; Julia Klemm, A chimera is not a pet 3 , 2025, steel, glaze, ceramic, pigment, 46 x 34 x 42 cm)

gouache paint, acrylic resin, biro, pencil, gesso and ink on wood. 31 x 24 x 5 cm; Julia Klemm, A chimera is not a pet 2,2025, steel, glaze, ceramic, pigment, 44 x 38 x 74 cm,; Julia Klemm, A chimera is not a pet 3 , 2025, steel, glaze, ceramic, pigment, 46 x 34 x 42 cm)

gouache paint, acrylic resin, biro, pencil, gesso and ink on wood. 31 x 24 x 5 cm,

There is a fascist, who lives in my head, and he has been there for a while. I speak to him almost everyday about different things, mainly things I see in the news or read about online, but sometimes also about art. Recently I was telling him about the fish, Kluzinger’s wrasse, which reminded me of a passage I read in “A Thousand Plateaus” by Deleuze and Guattari. They ascribe to a tropical fish an animal elegance, because of the way it uses its colourful design to blend in with its surroundings. The lines of the design are abstract and yet have the capacity to construct an entire underwater world.

Look, I tell him, we think we know what a fish is, the way you think you know what a dog or horse or lion is, an animal, a species, a type. Certainly your lot has made enough statues and animal monuments – porcelain shepherd dog figurines graced your tables. A fish lives in water and like all other fish has scales, fins and gills. We can compare this fish to another and note down the similarities of their characteristics, in order to classify them, genus: Thalassoma, family: Labridae. You think we know what kind of an animal a fish is. There it is. Put it in an aquarium.

Ah, I say, but can we see the animal Deleuze and Guattari describe as possessing an English kind of elegance? With a refinement that does not seek attention, but that remains quietly unobtrusive? This involves the appreciation of the small and the detailed, like those drain moths found in Jonathan Penca’s paintings, charming us with their fuzzy faces and furry wings. More than that, unobtrusiveness requires an effort. To go through life unnoticed is not easy and drain moths have a life cycle with four stages, larvae feeding on toilet sludge before developing into pupae.

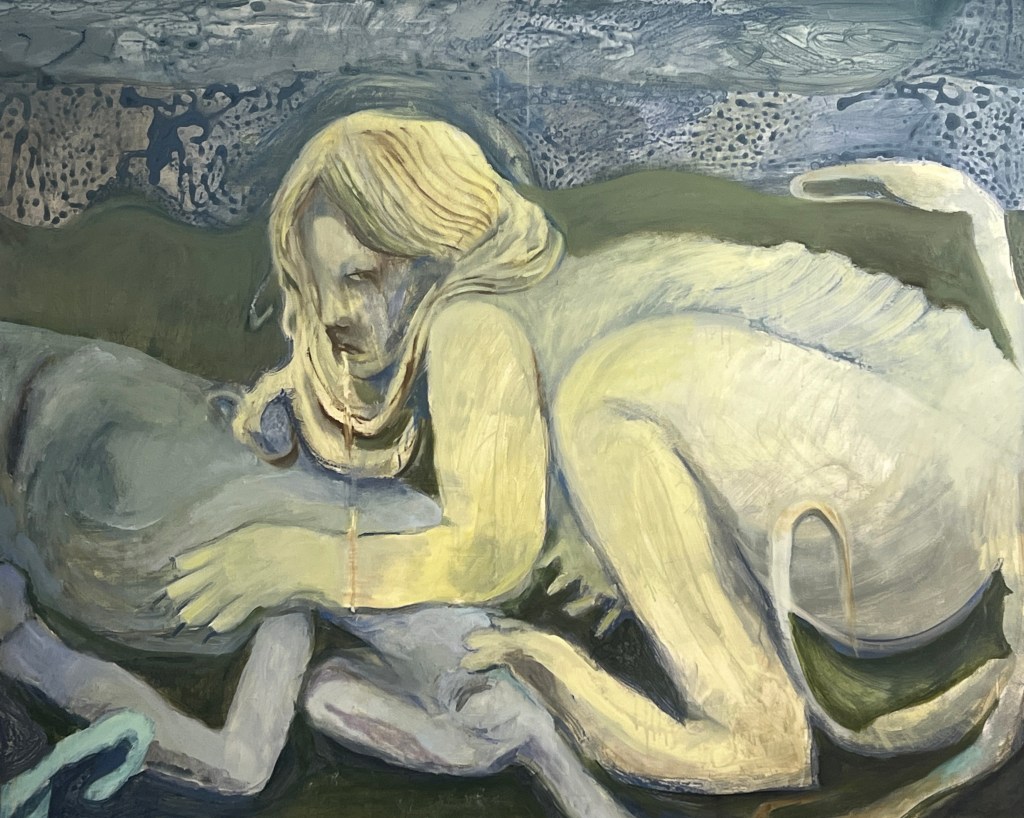

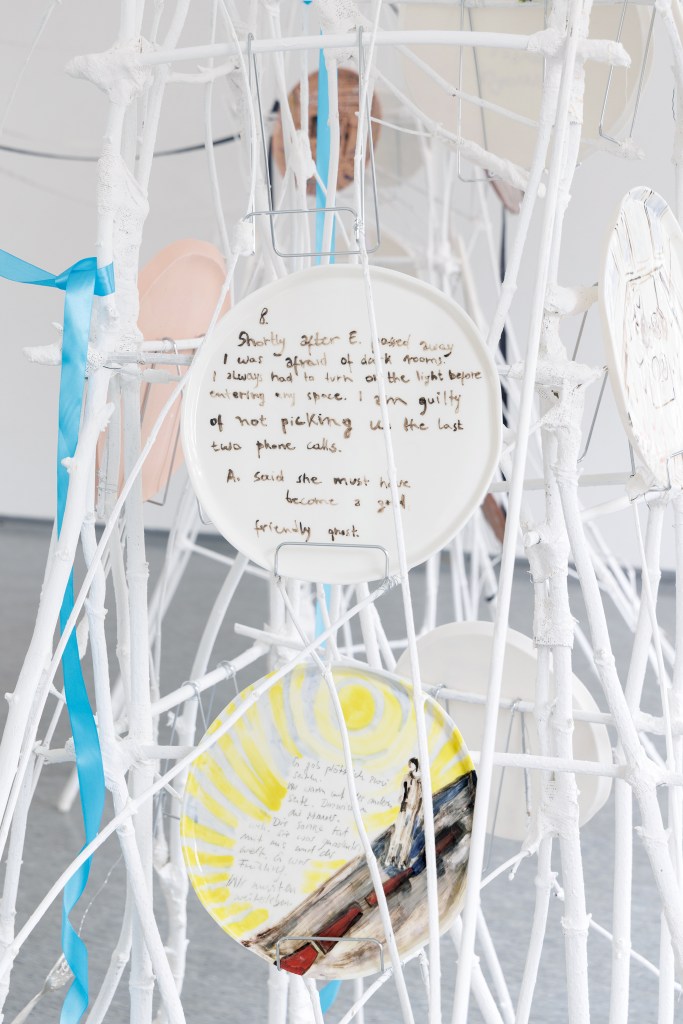

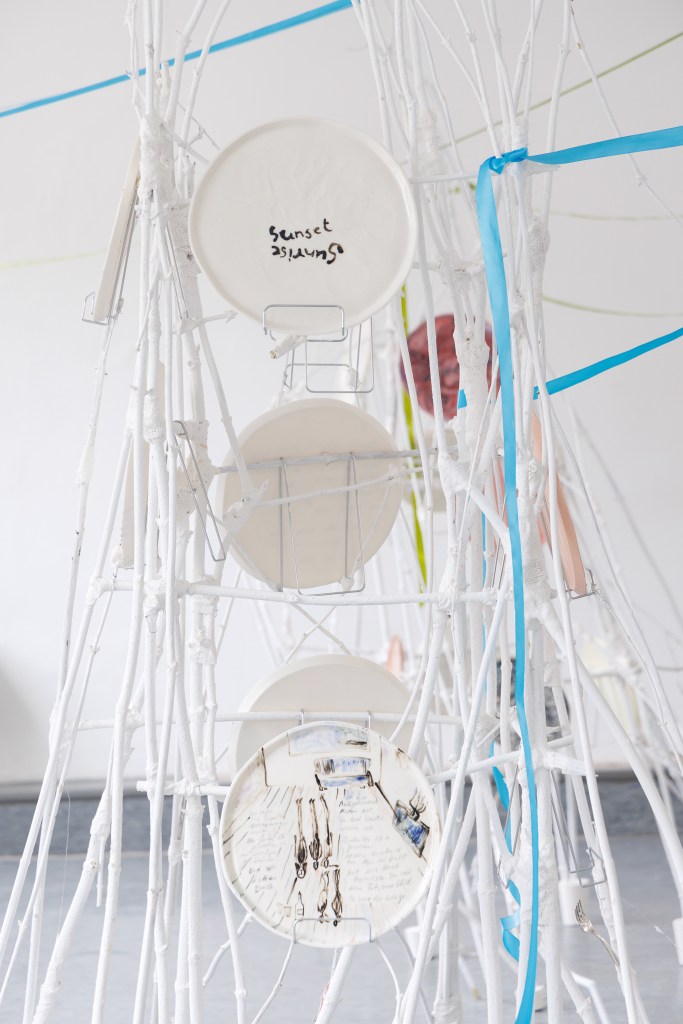

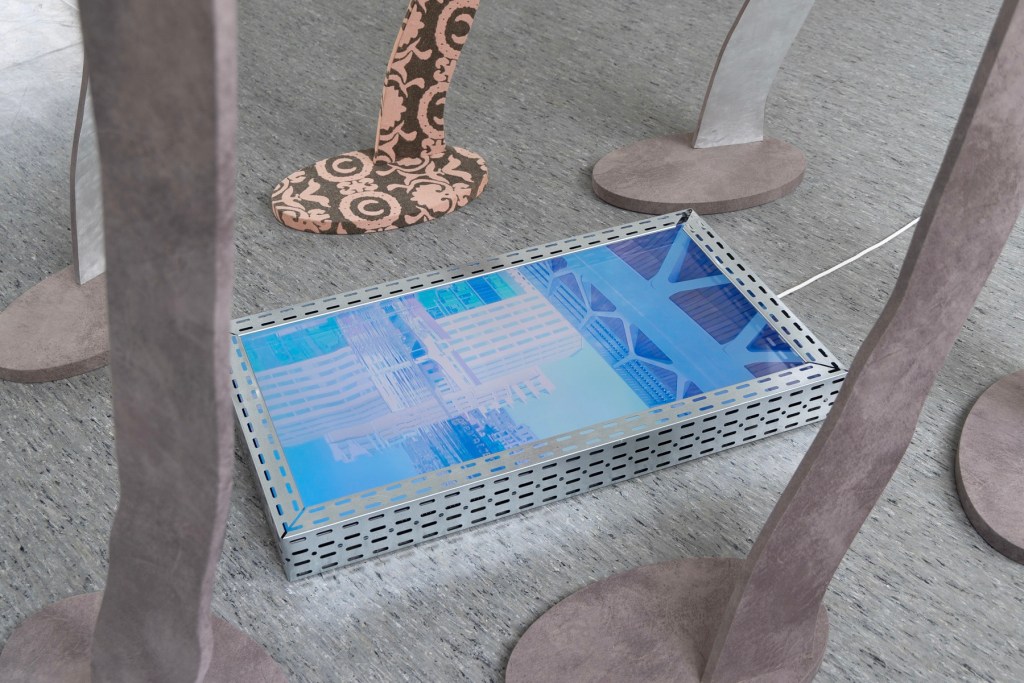

There are animals we see and animals we do not. The animals we do see, we organise and use, tame and breed. We control them as meticulously as Eadweard Muybridge did, when he set up multiple cameras to capture the image of the horse in motion or a lion in a cage, the starting point of Jakob Gilg’s paintings. We assign animals different roles: you there, you look soft and cuddly, you will be a pet. And you, you over there, so powerful and strong, you we will make into a symbol. Kitsch ceramic cats and scaled-down digital scans of lion monuments tumble, shatter and recombine in Julia Klemm’s work.

But this animal you don’t see, is something other than a molar entity, a different “affair” as Deleuze and Guattari would say, involving “becoming” not “being.” And it might seem we are meant to think this becoming morphologically, as the becoming of something else, a change from one permanent state to another, equally permanent one. A human could become a cat perhaps – or a cat, a human – as in the work of Anka Helfertova. Violence swirls around and we try to find our peace, not to lose ourselves within. To think becoming is to think loss, the elimination of all of our complaints, demands, unsatisfied desires, “everything that roots us in ourselves,” so that at the end, we are left with nothing, which is also everything. Becoming-animal is always a becoming-imperceptible, a shrinking best found in science fiction novels, the shrinking man becoming smaller and smaller without ever disappearing. Because when animals are thought in their becoming, the molecular comes into play, those invisible abstract forces that in their millions of interactions are actually responsible for constituting a world. To think an animal in its becoming is to engage with these molecular forces at work.

This is the demand elegance places on us: to think less of ourselves and more of the other. It is to be more attuned to our surroundings by paying attention to what continues to constitute us, which is always small and inorganic, indiscernible and impersonal. Elegance is a kind of molecular attention, but with a focus that opens out onto the world. To think things in their becoming molecularly is also to think in terms of the cosmos in its entirety. And then we might indeed stop seeing fish, but we will begin to see everything else.

Magdalena Wiśniowska 2025