Julia Klemm

28.06 – 26.07.2025

together with The Tiger Room at Heßstr. 48 b, 80798 Munich

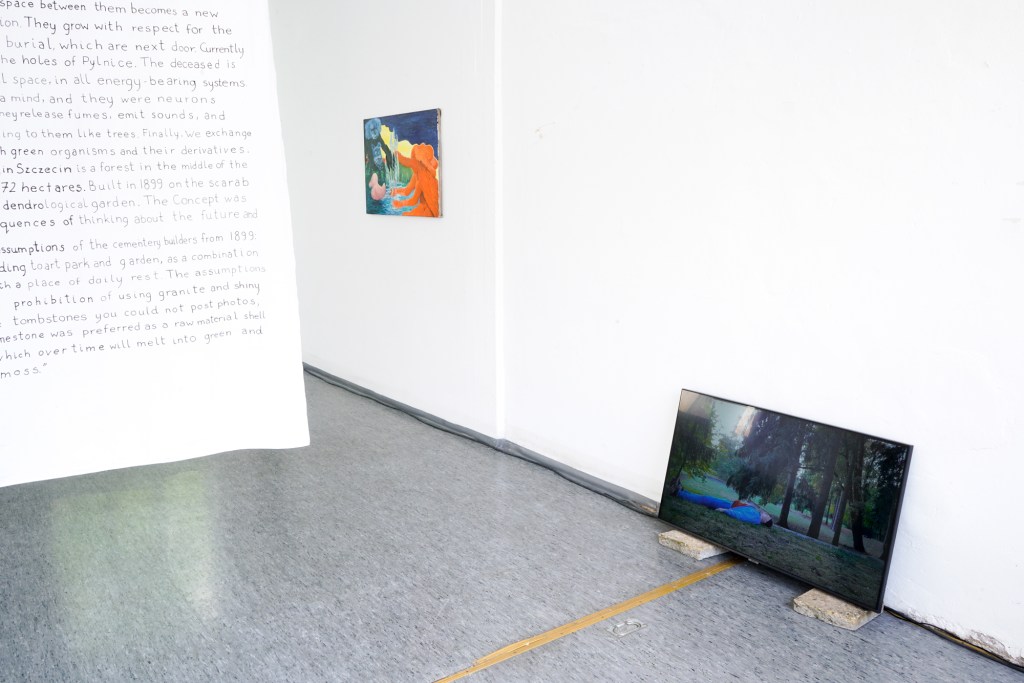

The problem I think, is that too often a chimera is seen as a pet. We visualise chimeras as these mythical fire breathing monsters, maybe with a lion’s head, a body of a goat, and a serpent for a tail. Three distinct animals are combined into one, their individual characteristics clearly visible for us to see. In contrast, biologically,a genetic chimera is often invisible, a nightmarish combination of two different sets of DNA, a result of one or more zygotes fusing together during the early stages of prenatal development. How this alien DNA might manifest is not altogether clear, but you hear stories of mothers having different DNA than their children, and the DNA from semen and saliva not matching in rape tests. To look for distinctions in chimeras would be the first step towards their domestication, treating the hybrid animal as another family member, a pet. But you cannot cuddle the long lost twin you might be carrying with you, inside.

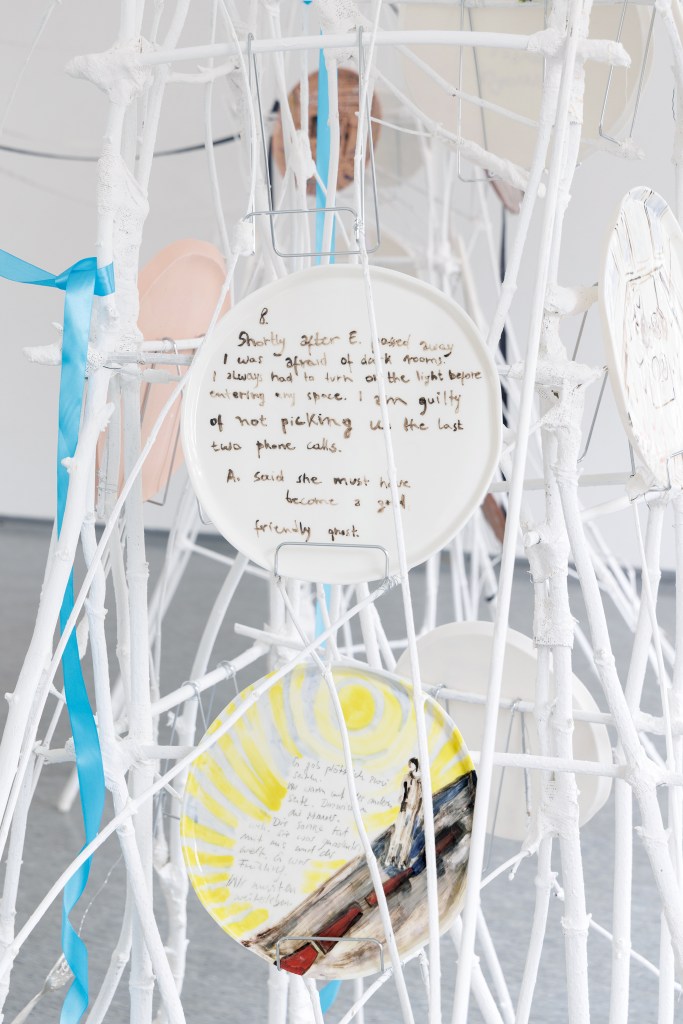

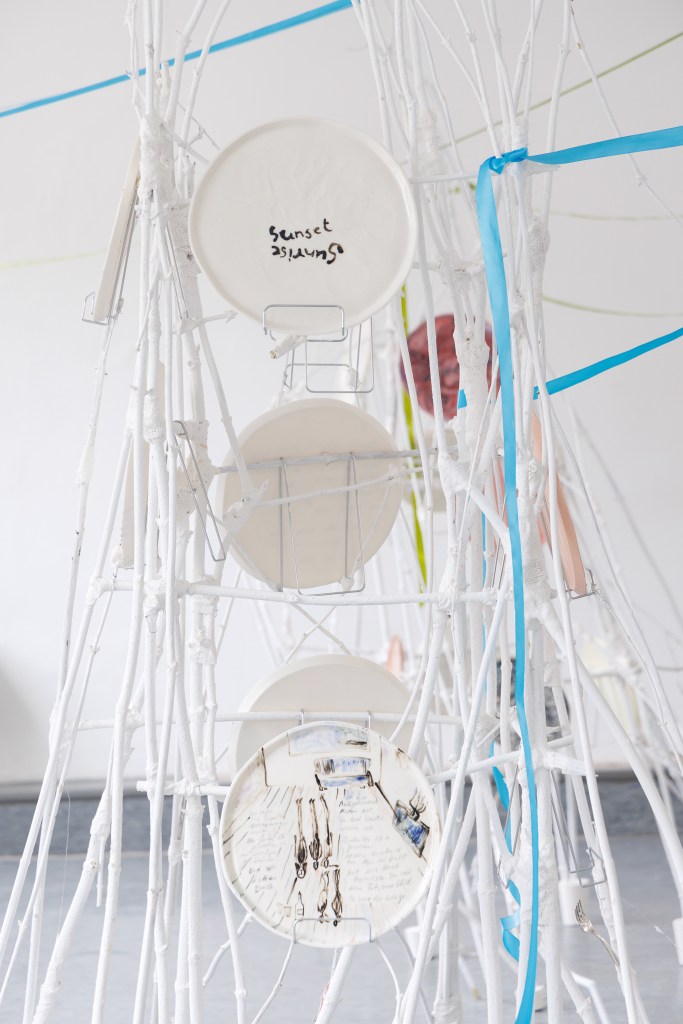

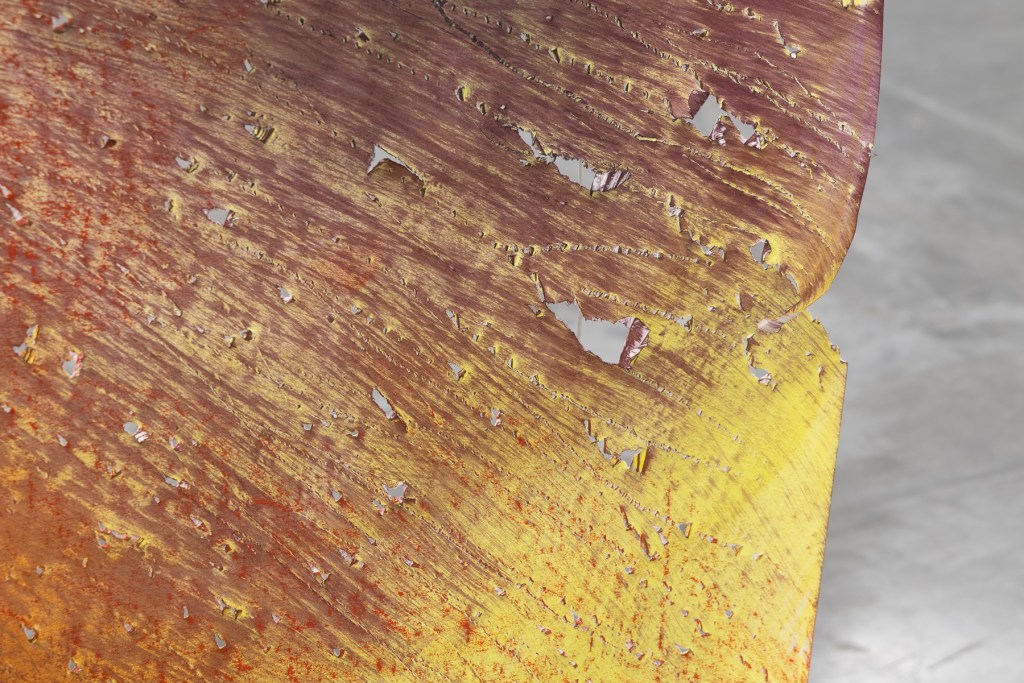

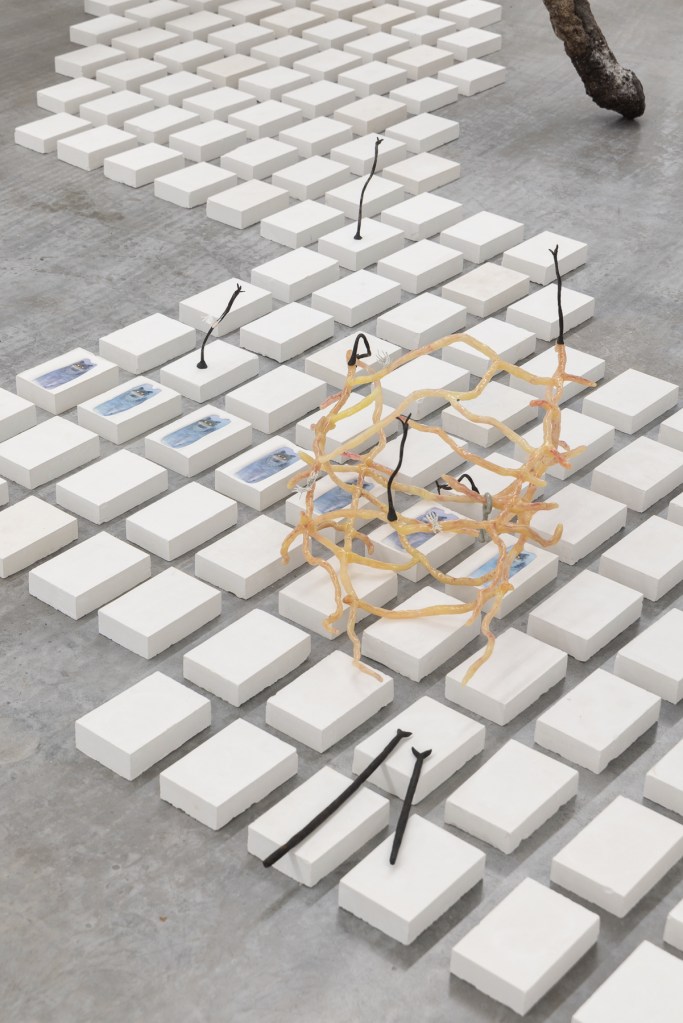

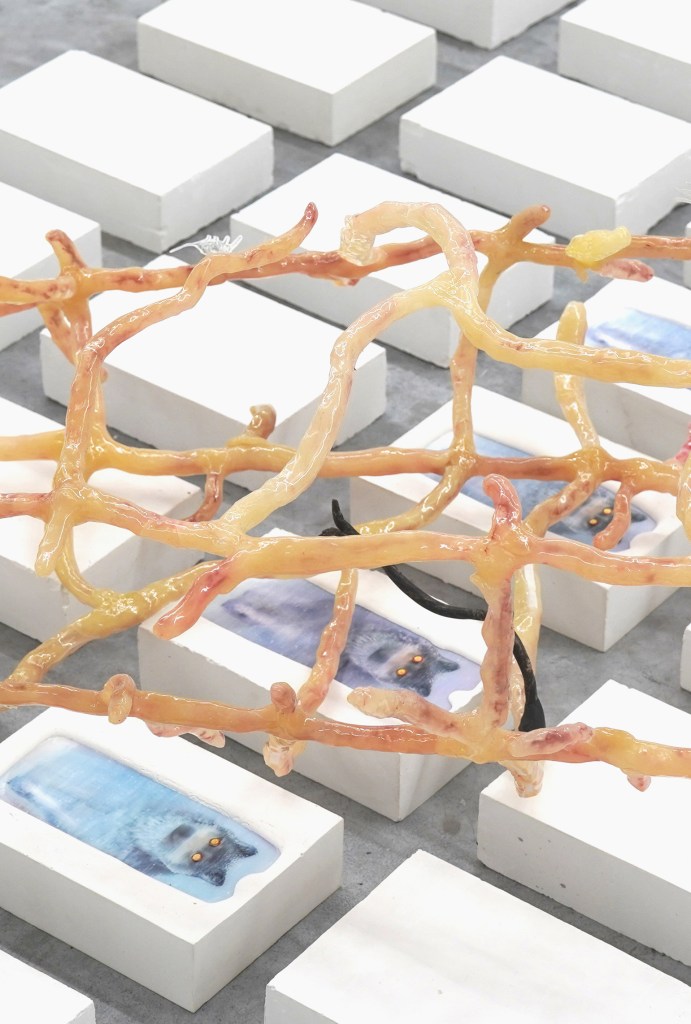

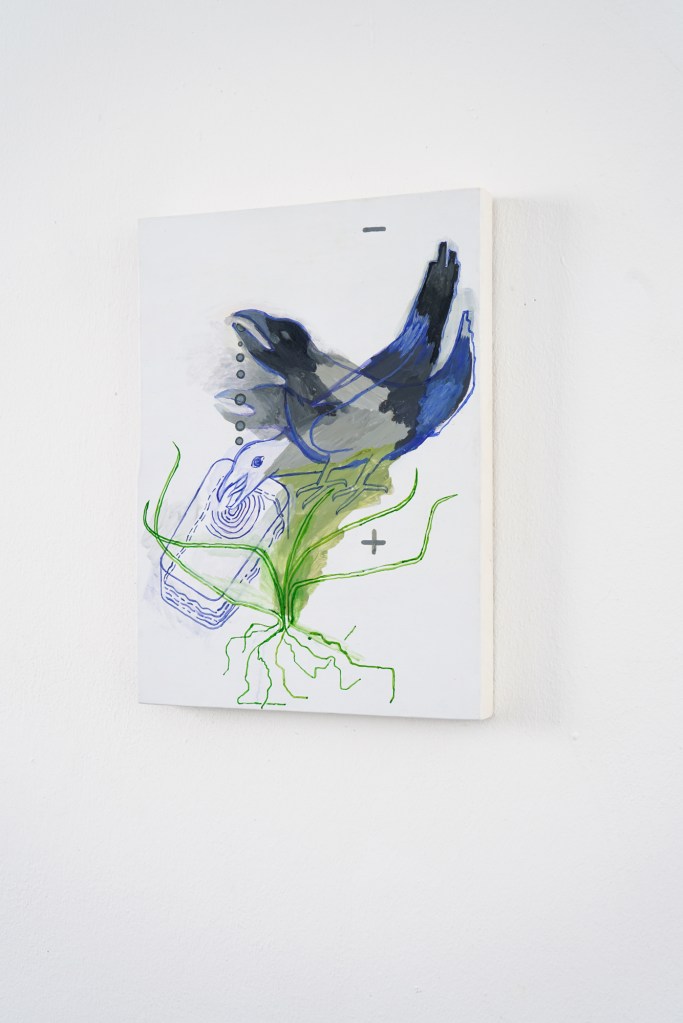

Julia Klemm’s ceramic work often involves a combination of several smaller ceramic pieces, each with their own specific animal DNA. Sometimes these are readymade figurines of cats, lions or horses, glossy and kitsch, inhabitants of Flohmärkte and Omas’ living rooms. At other times, these are recreations of existing public art, of lion statues such as those found on Odeonsplatz, scanned, scaled down and then modelled with a 3D-printed negative mould. Rarely, an animal-type structure is moulded in clay by Julia on the spot, traces of fur scratched with a serrated scraper onto its surface. These smaller animal ceramics are first broken, smashed into almost unrecognisable fragments before they are combined, their intertwining made permanent by the heat of the ceramic oven. I look for these fragments as I walk around the work and try to classify them: look, here are some lion’s legs, and here, a cat’s head, but upside down and half-broken, so that I can see the form inside and outside. Focussing on the surface helps, as I detect the glossy spots of a panther or the layer lines of the 3D printer.

In doing so, I am looking for a pet, with fur strokable like a pastel-coloured soft toy. I try to make the strange shapes of Julia Klemm’s work once again familiar to me. But their outward appearance is a result of a logic that remains hidden. The work demands I see it as a multiplicity, which means in animal terms, as a population. And science teaches us that a population is not a fixed set of individuals of the same species, but an always evolving, interacting mass that changes in relation to its location and environment. The alliances made in a population are not just of the filial kind between individual members of the group, but those made with other groups, other animals, with plants, and with geography. To see the inner workings of the animal in Julia Klemm’s ceramics, I need to step away from the animal and take a more expansive view, one that acknowledges population change forged by mutation. It is very alien to see the world in this way, as foreign and as violent as the shards of steel that interpenetrate the work, both holding it together and ripping it apart.

Magdalena Wiśniowska 2025