Another studio visit and resulting exhibition text:

I owe you the truth in painting and I will give it to you

Cézanne

…d’un seul pas franchi…

Derrida

The small problem of truth has been occupying me recently: the truth in painting, as promised by another “sauvage raffiné,” Paul Cézanne. A long time ago, it took a painting by Vincent van Gogh, Old Shoes with Laces (1886), for the German philosopher Martin Heidegger to recognise what this truth might be and for him, the artwork became defined through its revelation of this truth. We now consider ourselves too sophisticated to think that a painting of some worn-out shoes reveals something so profound about the peasant woman’s being that there is no other way this can be grasped. And yet a little of this heideggerian desire remains. I find we still look for truth in painting despite thinking it unlikely. Or at least, I do.

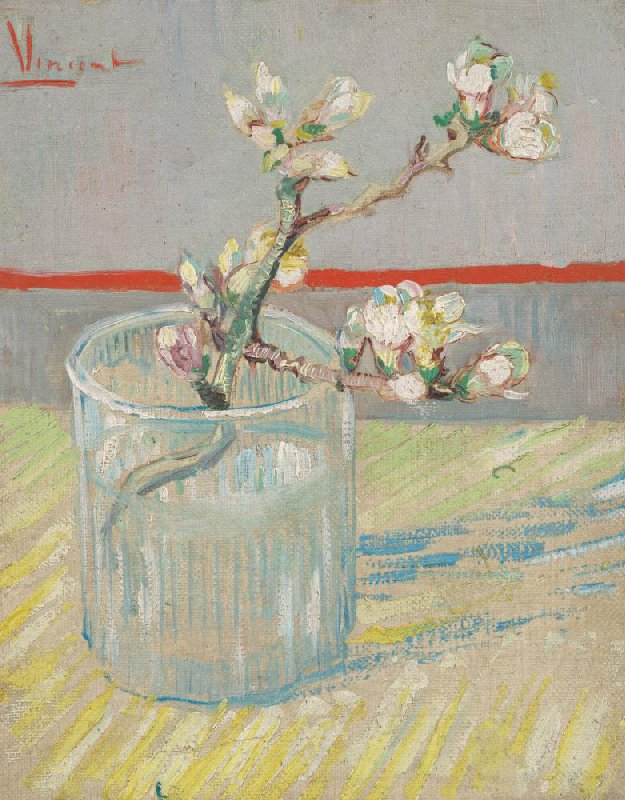

At the height of the pandemic Stefanie Ullmann would walk and run in the rose gardens at the Isar, in May, when the magnolias are in bloom. These caught her attention – I remember how bright that spring was, and how vibrant the greens. But again it took a painting by van Gogh, this time, Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass (1888) for her to begin painting from memory a series of small canvases with flowers. A second series of watercolours followed. The oil paintings share van Goghs’ shimmering green-yellow palette as well as his strong horizontal and vertical lines.

Credits: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

When I look at these paintings I find myself standing in Heidegger’s shoes. There is a truth in Stefanie Ullmann’s work that has to do with his schematic definition. On the one hand he claims, art has long been thought as formed matter, in other words as a “Zeug,” translated by Derrida as a “product,” more commonly in English translations of Heidegger’s essay as “equipment.” And these paintings here, especially the abstract ones, have this workman-like quality of being built, almost brick by brick, layer by layer. Occasionally Stefanie Ullmann even uses a spatula like a masonry trowel. And yet, as Derrida in his interpretation of Heidegger’s argument rightly notes, an artwork is more than a product or Zeug because it does what no other product can – it resembles a thing, “Ding.” It is as if it were not produced. Thus, an artwork is a product that is also more than a product, because it crosses over, steps into the realm of the thing. In the same way, Ullmann’s paintings enjoy this self-sufficiency. Despite their lightness, they feel as sturdy as earth or rock or tree, untouched by human hand.

The point of painting is – for Van Gogh, Heidegger, Derrida etc. – that this step crossing from thing to product and back again occurs within. Painting shows how tightly things, Zeug and artworks interlace.