Sophia Mainka

in collaboration with Fondation Fiminco, Paris

6.09 – 13.10.2023

Lothringer 13 Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

Photos: Thomas Spelt

In the summer of 2022, a Beluga whale strayed into the river Seine and began swimming towards Paris. It was stopped by a lock, refused to eat and was subsequently euthanised. Nobody knows when parrots entered Parisian airspace, but they have been observed in the French capital since the 1970s. They can now be seen in most of Paris’s public parks, from the Bois de Boulogne in the west to the Bois de Vincennes in the east. And dogs – well, dogs have been roaming Parisian streets since forever. Terriers, Dachshunds, Spaniels, and of course, the French Bulldog.

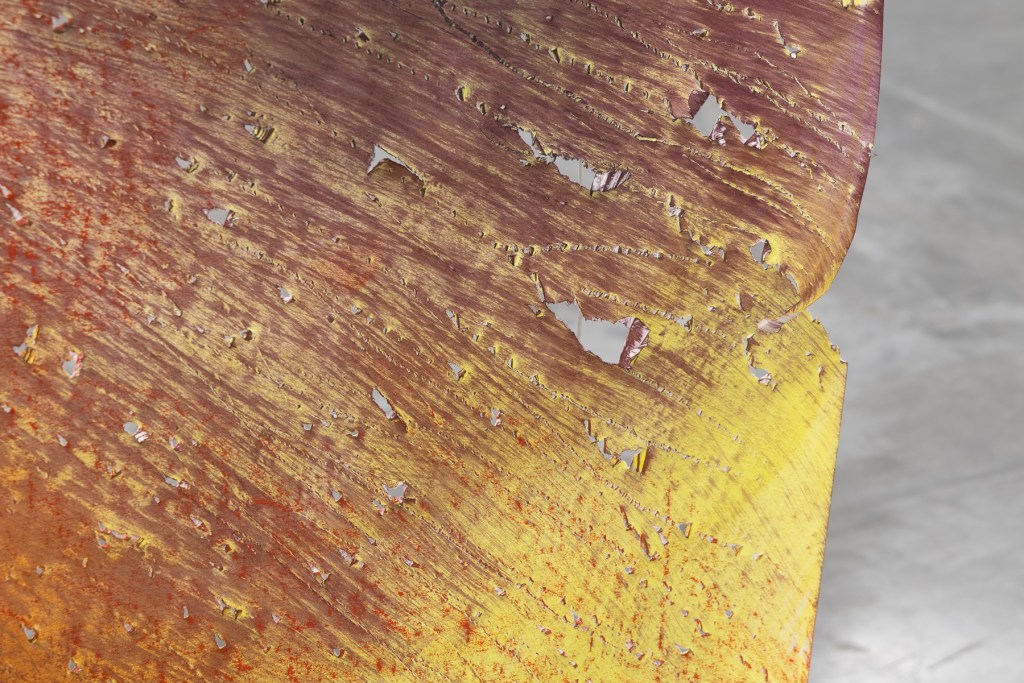

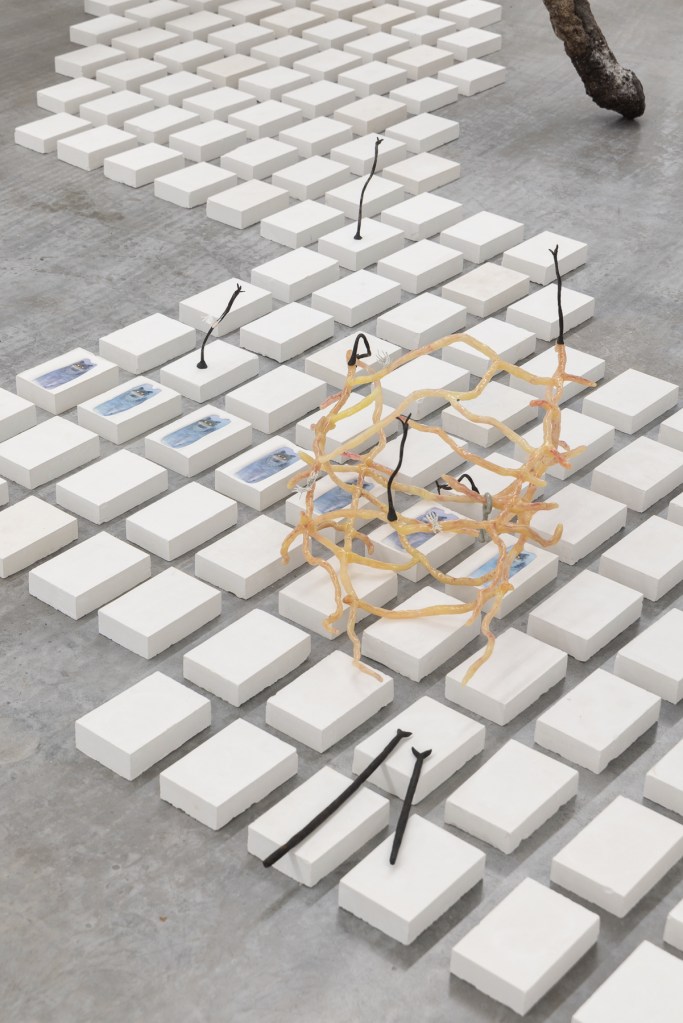

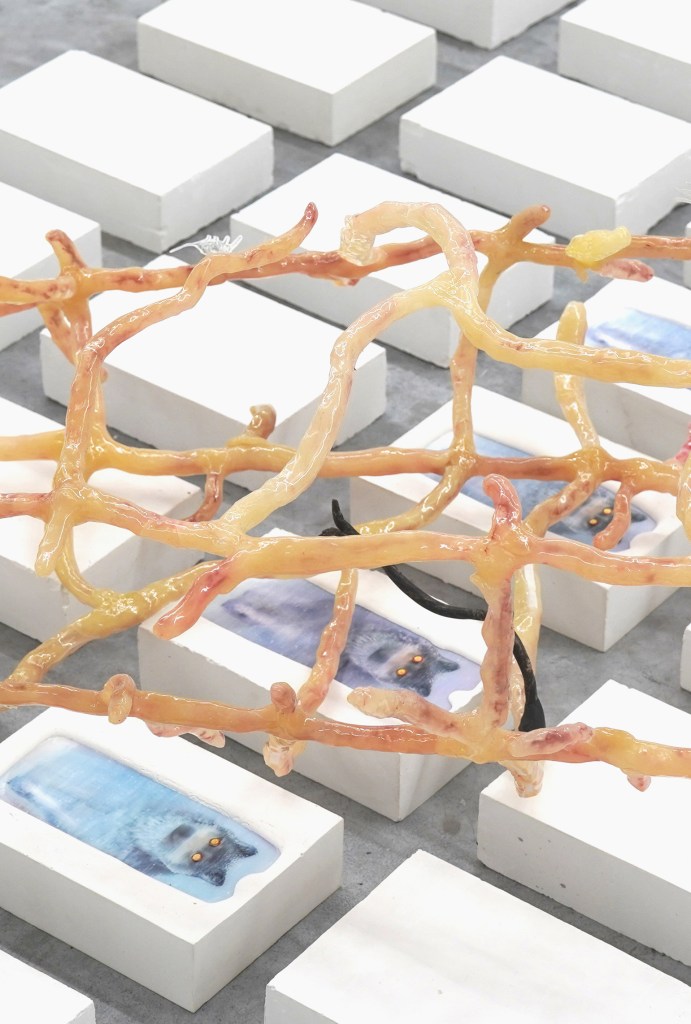

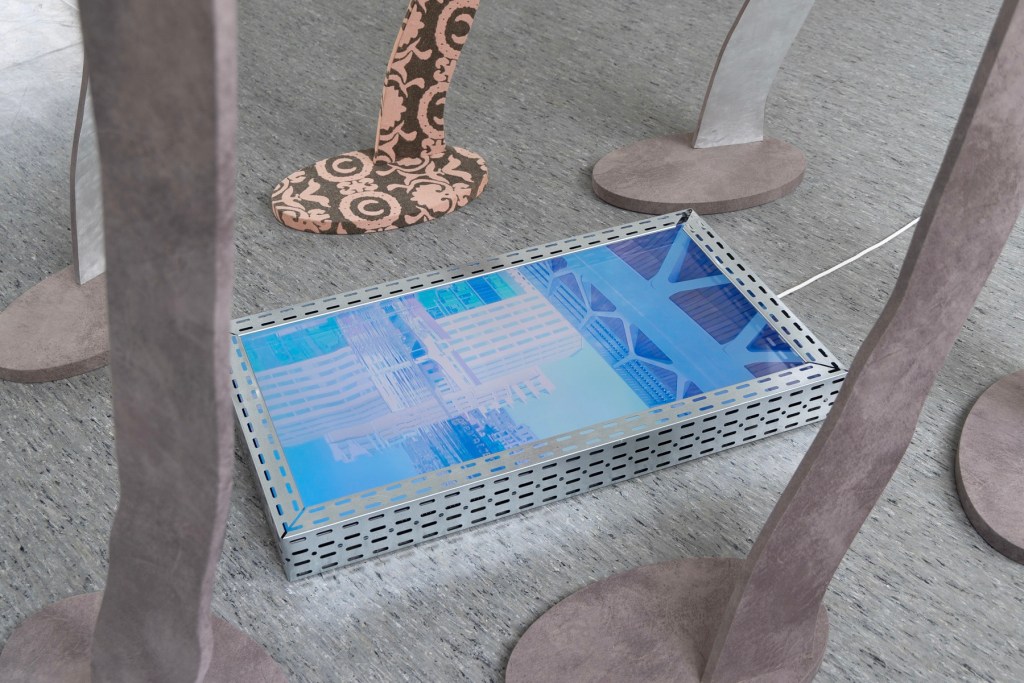

These stories of animals adapting to urban environments lay at the heart of Sophia Mainka’s video and sculpture installation, “Notes on Roommates (a dog, a parrot, a whale and a canal)” produced and first shown during her residency at Fondation Fiminco in Paris. Amid the organic playful forms of the metal sculptures there are three videos, all filmed from the animal perspective. In the first two, Mainka paints her arms and hands to resemble a dog’s paws, and we see these on screen as the fictional dog walks, stops and occasionally runs around the cobblestones and concrete pavements, once even jumping from a wooden bench. In the third, she takes on the perspective of the whale, the camera capturing what the whale would have seen, providing it swam further, into the city canals. The image rises and dips to the rhythm of the whale’s breathing. Surrounding us are the sounds of birds singing, except this too is staged: these are not parrots, but a toy, a bird whistle device.

Her work then, could be described as ethological in spirit. Sophia Mainka does not imitate animals, but rather behaves like them. She scratches, she sniffs, she swims, she trills and peeps. She acts the way an animal would act, if she were a animal in this situation and in this sense, we can think of her work in terms of what the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze would call becoming.

For Deleuze and Guattari, the process of becoming-animal is best described by Vladimir Slepian in his short text, “Fils de Chien.” Written in the first person, Slepian confesses how, despite being a man, his hunger leads him to behave like a dog, putting shoes on his hands and tying them using his mouth. It is a reversal of the evolutionary process described by anthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan, in which humans, through their adoption of an upright posture, free their mouths from the task of grasping and develop speech. Slepian recomposes himself, so that his mouth instead of speaking, grasps like a dog’s. And it is irrelevant how this dog looks like, whether this is the short snout of a bulldog or longer nose of a dachshund.

Similarly, Mainka makes us rethink our relation to nature, which is redrawn along affective lines as a participatory process. Animals are not considered as distinct molar entities, standing alongside the human. All entities are defined by their capacity to act, which changes depending on how they affect and how they are affected by others. There is a sensing of utopia in the environs of the Canal Saint-Martin that Mainka would walk along so happily – a secluded, sheltered place of inter-species co-existence. Or rather, it is a place where different populations, human, mammal and bird, continually compose and re-compose together.

Im Sommer 2022 verirrte sich ein Belugawal in die Seine und begann, in Richtung Paris zu schwimmen. Er geriet in eine Schleuse, fraß nicht mehr und wurde daraufhin eingeschläfert. Seit wann genau Papageien sich im Pariser Luftraum angesiedelt haben, ist unklar, aber sie werden seit den 1970ern in der französischen Hauptstadt beobachtet. Heute kann man sie in den meisten öffentlichen Parks der Stadt entdecken, vom Bois de Boulogne im Westen bis zum Bois de Vincennes im Osten. Und Hunde – nun ja, Hunde streifen seit jeher durch die Pariser Straßen, ob Terrier, Dackel, Spaniel und natürlich die französische Bulldogge.

Diese Erzählungen von Tieren, welche sich an urbane Lebensräume anpassen, stehen im Zentrum von Sophia Mainkas Installation “Notes on Roommates (a dog, a parrot, a whale and a canal)“ aus Videos und Skulpturen, die während ihres Residenzaufenthalts in der Fondation Fiminco in Paris produziert und dort auch zum ersten Mal gezeigt wurde. In die organischen und spielerischen Formen der Metallskulpturen sind drei Videos integriert, alle aufgenommen aus der Tierperspektive. Im ersten und zweiten Video sind Mainkas Arme und Hände wie Hundepfoten bemalt. Wir nehmen den Blickwinkel jenes fiktiven Hundes ein, laufen mit ihm über Kopfsteinpflaster und Bürgersteige, halten plötzlich an, rennen hin und her und springen einmal sogar von einer Holzbank. Im dritten Video nimmt Mainka die Perspektive des Wals ein, wobei die Kamera das wiedergibt, was jener wohl gesehen hätte, wenn er weiter in die Stadt hinein geschwommen wäre. Das Bild bewegt sich im Rhythmus der Atmung des Wals. Um uns herum erklingt Vogelgezwitscher, aber auch das ist eine Inszenierung: Es sind keine Papageien, sondern ein Spielzeug, eine Vogelpfeife.

Man könnte Sophia Mainkas Arbeit durchaus als ethologisch bezeichnen. Die Künstlerin imitiert keine Tiere, sondern verhält sich wie sie. Sie kratzt, schnüffelt, schwimmt, trällert und piepst. Sie verhält sich so, wie ein Tier sich verhalten würde, wenn sie ein Tier in dieser Situation wäre, und wir können ihre Arbeit im Sinne dessen betrachten, was der französische Philosoph Gilles Deleuze als Werden bezeichnen würde. Am besten wird der Prozess der Tierwerdung für Deleuze und Guattari von Vladimir Slepian in seinem kurzen Text “Fils de Chien“ beschrieben. In der ersten Person verfasst, bekennt Slepian, dass er sich, obwohl er ein Mann sei, aus Hunger wie ein Hund benehme, indem er sich Schuhe an die Hände binde und sie mit dem Maul zubinde. Dies ist eine Umkehrung des vom Anthropologen André Leroi-Gourhan beschriebenen evolutionären Prozesses, bei dem der Mensch durch die Entwicklung einer aufrechten Körperhaltung seinen Mund von der Aufgabe des Greifens befreit und Sprache entwickelt. Slepian setzt sich neu zusammen, so dass sein Mund nicht mehr spricht, sondern wie der eines Hundes zupackt. Dabei ist es unerheblich, wie dieser Hund aussieht, ob er die kurze Schnauze einer Bulldogge oder die längere Nase eines Dackels hat.

In ähnlicher Weise regt Mainka uns dazu an, unsere Beziehung zur Natur zu überdenken, wobei dieses Verhältnis entlang affektiver Linien zu einem partizipatorischen Prozess umgestaltet wird. Tiere werden nicht als getrennte molare Einheiten neben dem Menschen betrachtet, sondern alle Lebewesen werden durch ihre Handlungsfähigkeit definiert, die sich verändert, je nachdem, wie sie auf andere einwirken und wie sie von anderen beeinflusst werden. In der Umgebung des Canal Saint-Martin, an dem Mainka so gerne spazieren geht, ist ein Hauch von Utopie zu spüren – ein beschützter, ruhiger Ort, an dem verschiedene Arten koexistieren. Oder genauer gesagt: Es ist ein Ort, an dem sich verschiedene Spezien, ob Menschen, Säugetiere oder Vögel, immer wieder neu zusammensetzen.