Susanne Kühn

07.09. – 12.11.2023

Lothringer 13 Studio, Lothringer Str. 13, 81667 München

Photo credit: Bernhard Strauss

Photo: Bernhard Strauss

Photo: Bernhard Strauss

Photo: Bernhard Strauss

Photo: Bernhard Strauss

It begins with the amoeba, like the one we drew at school: flower-like, dotted with vacuoles, a circular nucleus in the middle. An amoeba, despite not having a brain, a nervous system or indeed any kind of sensory cells, can react. It moves around the murky pond water that makes up its environment, finding food, avoiding predators, anticipating, reacting. It has no need for organs. Organs developed later, in the course of evolution, as a means fulfilling functions to a higher degree. An organism with a brain, can think better than an organism without one.

French philosopher Raymond Ruyer considers all organs to be technical artefacts, technologies developed by the organism as it evolved. By having a brain and a nervous system, we have access to technologies an amoeba doesn’t have and this makes us feel sophisticated. We can make complex decisions, solve problems and form concepts, leaving murky pond water behind.

Like in Susanne Kühn’s paintings, there is no line between the artificial and the nature. If the organ is a technical artefact, it does not differ from the other artefacts, those tools and machines that we surround ourselves with. The organ belongs to an internal proto-technicity, while the machine is the externalised projection of the organ. Each also has its own evolutionary trajectory, one internal, the other external, an exo-darwinism.

In the painting “Robota I” we see the artist in three different guises: as St. Barbara reading, as a young woman in East Germany working, and as a mother tending the fireplace. Three technologies are depicted here, all extensions of the body. There is the book, the pool of knowledge, acting as an extension of the brain. Tools and machines such as found in a factory are extensions of the human hand. Fire, to keep us warm and to heat up food, is the most primitive of technologies, an extension of our thermoregulation and digestive system. Working with these technologies makes up the life of the artist.

Similarly, the biological has a technological aspect in “Her name is Amygdala Vertigo.” The reference is to the amygdalae, two bean-shaped clusters of deep within the cerebrum of the brain, which we learn are responsible for memory, decision making and emotional response. Diagrammatically, they look like the EarPods which seem to sprout out of the picture frame, softly-curved and convex. They are surrounded by the sharp, multicoloured concave curves of the hand ax, one of the first man-made tools. The portrait is of an extended body, spread over various technologies depicted on the canvas.Foremost, Susanne Kühn is interested in those moments in which the forward pushing trajectory of evolution and technological development foams up in bubbles of effervescence. Her painting is not of lines which separate, marked by horizontal and vertical coordinates – the sharp perspective she often uses, stutters quickly in her work. Hers are lines without connecting points.

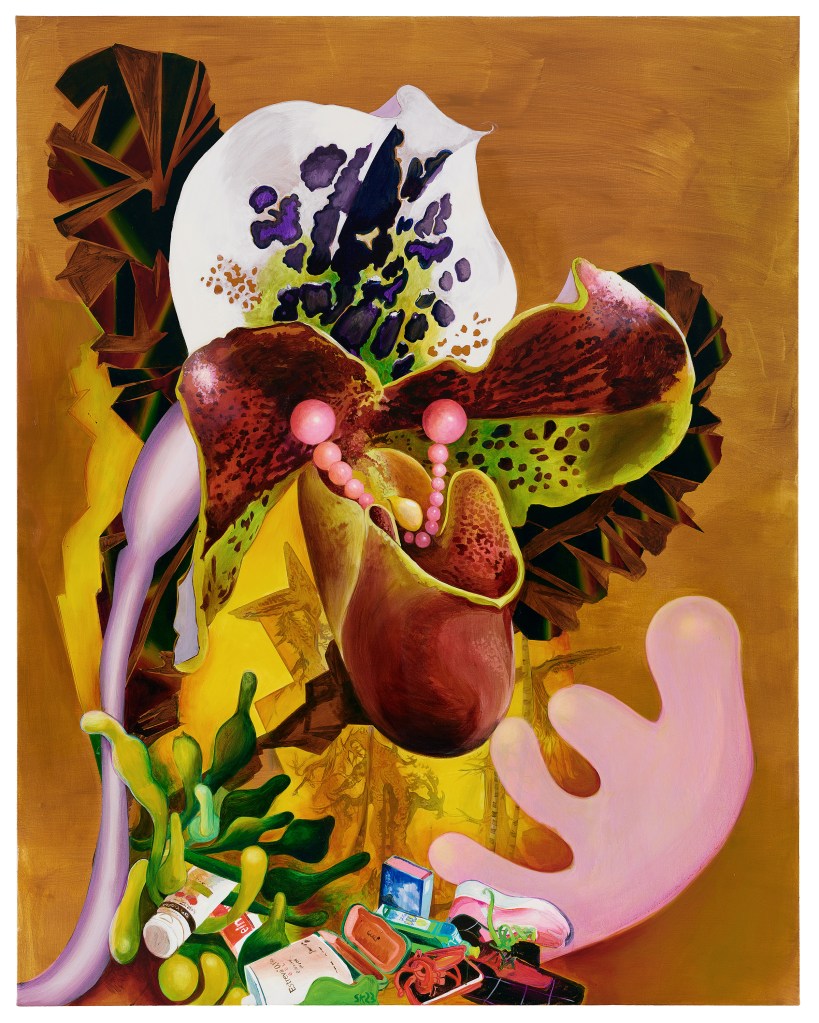

“Frauenschuh – Lady’s slipper” is a self-portrait, the mess of detritus standing in for the technologically extended body: we see a smartphone, medication for the menopause, a sneaker, toothpaste. The flower itself is a cultivated hybrid, its natural evolution determined by man. In this work, the extended body of man, is also a body outside of the dictates of evolution, a “deterritorialised” body no longer adapted to any particular environment. A “deterritorialised” hand is nothing more than a useless pink cartoon blob. It ends with the amoeba in the pond, the water now an acid yellow, surrounded by toxic corals and water plants.

Magdalena Wisniowska 2023

Es begann mit der Amöbe, wie wir sie in der Schule gezeichnet haben: blütenförmig, mit Vakuolen übersät, mit einem kreisförmigen Zellkern in der Mitte. Obwohl die Amöbe weder ein Gehirn, noch ein Nervensystem oder Sinneszellen hat, besitzt sie die Fähigkeit auf ihre Umgebung zu reagieren. Auf der Suche nach Nahrung bewegt sie sich im trüben Teichwasser, weicht Fressfeinden aus, antizipiert und reagiert. Dafür braucht sie keine Organe, denn erst im Laufe der Evolution entwickeln sich diese, um komplexere Funktionen erfüllen zu können. Ein Organismus mit einem Gehirn kann besser denken als ein Organismus ohne Gehirn.

Für den französischen Philosophen Raymond Ruyer sind alle Organe technische Artefakte; Technologien, die der Organismus mit der Zeit entwickelt hat. Im Gegensatz zur Amöbe haben wir durch unser menschliches Gehirn und unser Nervensystem Zugang zu diesen Technologien. Das gibt uns das Gefühl, hoch entwickelt zu sein. Wir sind in der Lage, komplexe Entscheidungen zu treffen, Probleme zu lösen und Konzepte zu entwickeln, und lassen dabei das trübe Teichwasser hinter uns.

In den Gemälden von Susanne Kühn gibt es keine Grenze zwischen dem Künstlichen und der Natur. Ist das Organ ein technisches Artefakt, unterscheidet es sich nicht von den anderen Artefakten; den Werkzeugen und Maschinen, mit denen wir uns umgeben. Das Organ gehört zu einer inneren Proto-Technizität, während die Maschine die externe Projektion des Organs ist. Beide haben zudem ihre eigene evolutionäre Entwicklung, die eine intern, die andere extern, ein Exo-Darwinismus.

Im Gemälde “Robota I” sehen wir die Künstlerin in drei verschiedenen Gestalten: als lesende Heilige Barbara, als junge Frau in Ostdeutschland bei der Arbeit und als Mutter, die das Feuer anfacht. Drei Technologien werden hier dargestellt, allesamt Erweiterungen des Körpers. Da ist das Buch: der Wissensspeicher, der als Erweiterung des Gehirns fungiert. Werkzeuge und Maschinen sind Erweiterungen der menschlichen Hand. Mit dem Feuermachen wärmen wir uns und bereiten Nahrung zu. Es ist die primitivste aller Techniken, sie ist eine Erweiterung unseres Thermoregulations- und Verdauungssystems. Die Arbeit mit diesen Technologien bildet das Schaffen der Künstlerin.

In ähnlicher Weise hat das Biologische einen technischen Aspekt in “Her name is Amygdala Vertigo”. Im menschlichen Gehirn besteht die Amygdala aus zwei tiefsitzenden mandelförmigen Zellstrukturen, die, wie wir lernen, für Gedächtnis, Entscheidungsfindung und emotionale Reaktionen zuständig sind. Schematisch gesehen gleichen sie den EarPods, die aus dem Gemälde herauszuwachsen scheinen, sanft gebogen und konvex. Sie sind umgeben von den scharfen, vielfarbig konkaven Kanten des Faustkeils, einem der ersten vom Menschen hergestellten Werkzeuge. Das Porträt, als „extended body“, beinhaltet die auf der Leinwand dargestellten Technologien.

Susanne Kühn interessiert sich vor allem für jene Momente, in denen das Fortschreiten der Evolution und der technologischen Entwicklung aufschäumen. Die klaren Linien ihrer Malerei entstammen keinem präzisen Koordinatensystem, vielmehr zerbricht das perspektivische Konstrukt des Bildes schnell. Ihren Linien fehlen die Verbindungspunkte.

“Frauenschuh” ist ein Selbstporträt, in dem die Ansammlung von nicht abbaubarem Müll für den technologisch erweiterten Körper steht: Wir sehen ein Smartphone, Medikamente für die Wechseljahre, einen Turnschuh, Zahnpasta. Die Blume selbst ist eine gezüchtete Hybride, deren natürliche Entwicklung vom Menschen bestimmt wurde. In diesem Gemälde ist der erweiterte Körper des Menschen auch ein Körper außerhalb des Diktats der Evolution, ein “deterritorialisierter” Körper, der nicht mehr an eine bestimmte Umgebung angepasst ist. Eine „deterritorialisierte“ Hand ist nichts weiter als ein nutzloser rosa Cartoon-Klecks.

Es endet mit der Amöbe im Teich, dessen Wasser nun säuregelb ist, umgeben von giftigen Korallen und Wasserpflanzen.

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

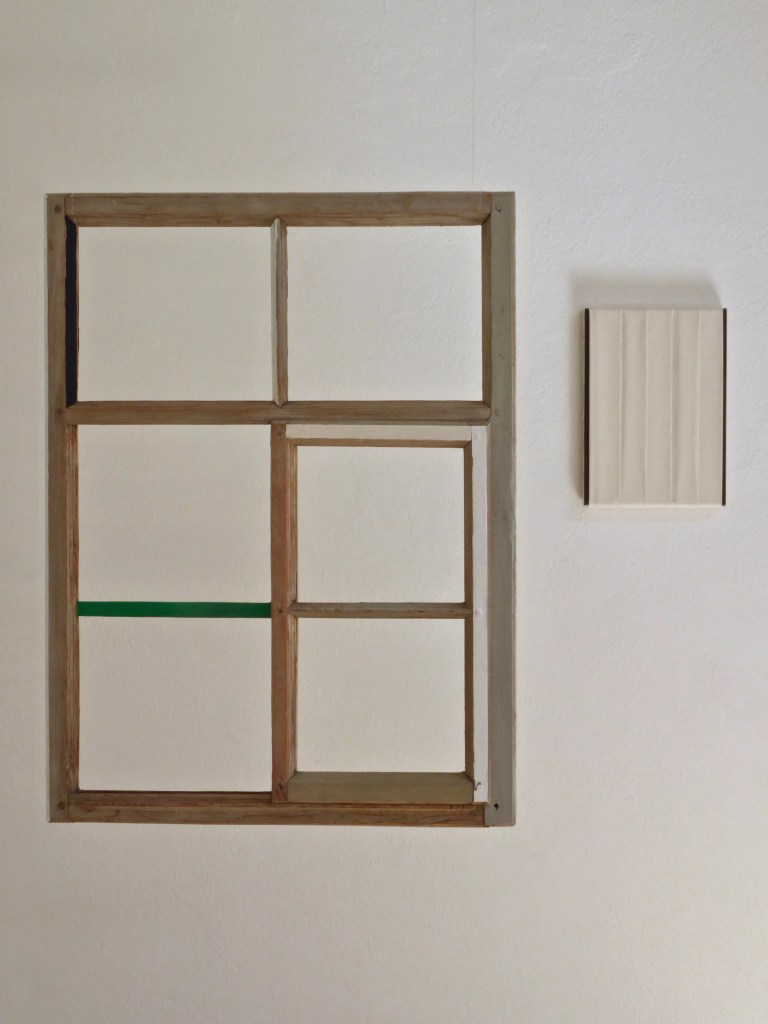

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, untitled, 2019, antique wooden windowframe and egg tempera, dimensions variable

Justina Becker, untitled, 2019, antique wooden windowframe and egg tempera, dimensions variable Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

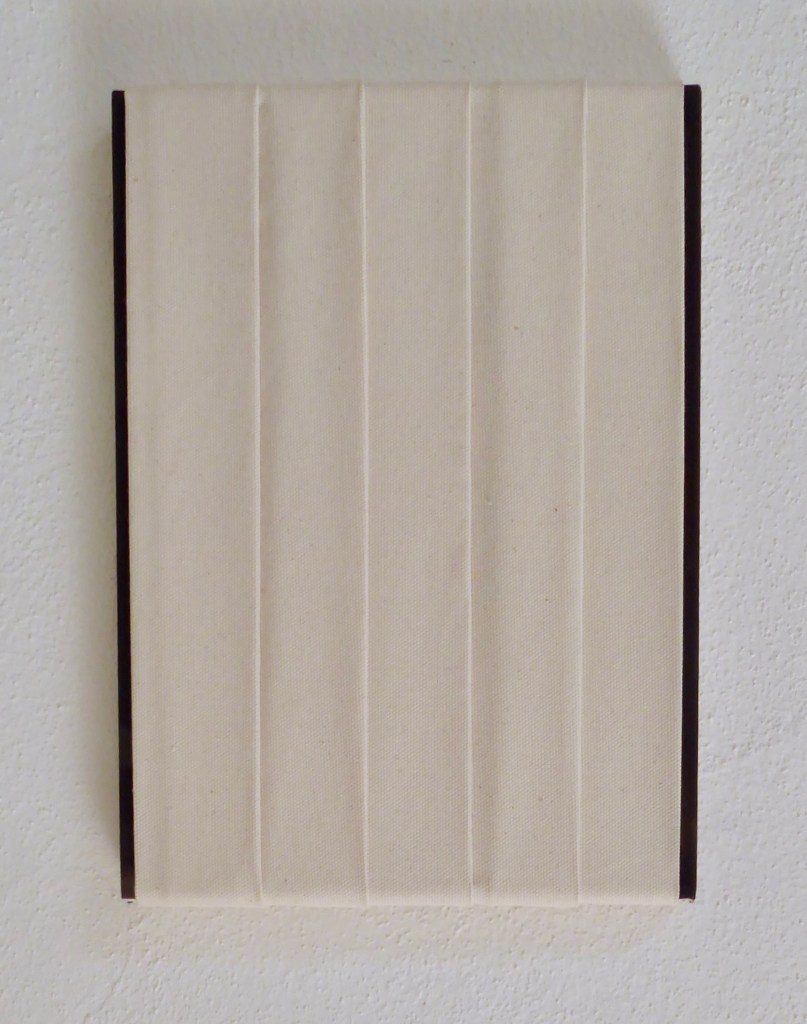

Justina Becker, o.T., 2015, egg tempera and canvas strips, 20 x 32 cm

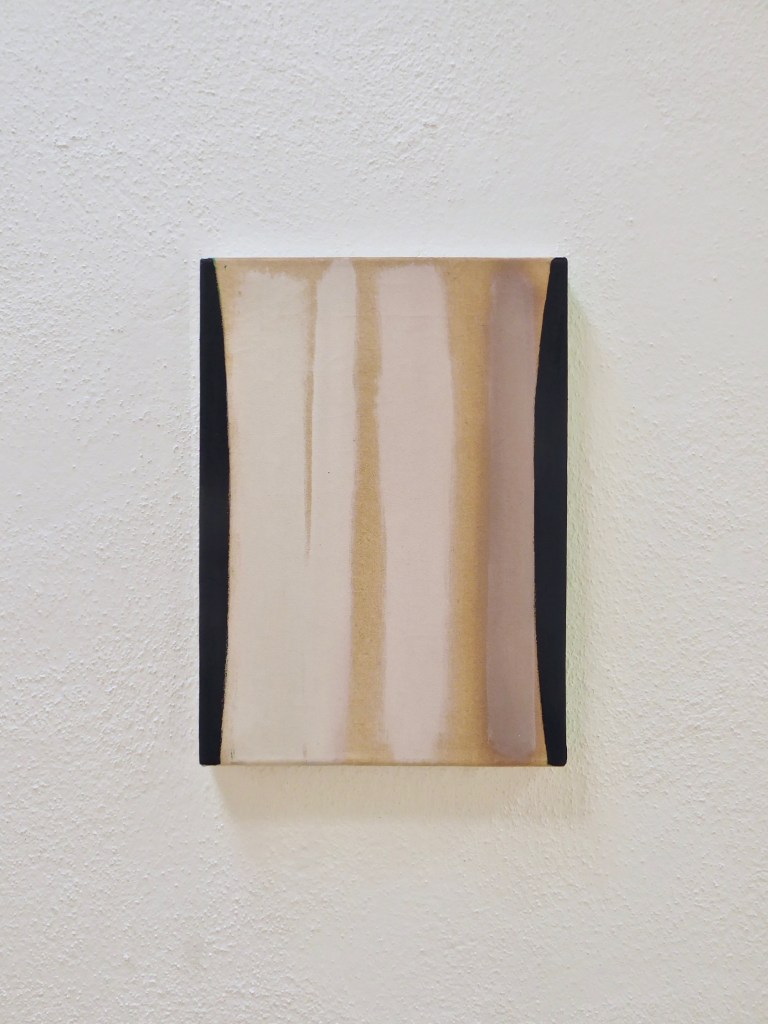

Justina Becker, o.T., 2015, egg tempera and canvas strips, 20 x 32 cm Justina Becker, o.T., 2015, egg tempera on canvas, 20 x 32 cm

Justina Becker, o.T., 2015, egg tempera on canvas, 20 x 32 cm Justina Becker, o. T., 2015, egg tempera on canvas,

Justina Becker, o. T., 2015, egg tempera on canvas, Justina Becker, 2019, installation view

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime)

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime) Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime)

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime) Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime)

Justina Becker, 2019, installation view (nighttime)